PART ONE

TO THE END OF THE MIDDLE AGES

THE AREA

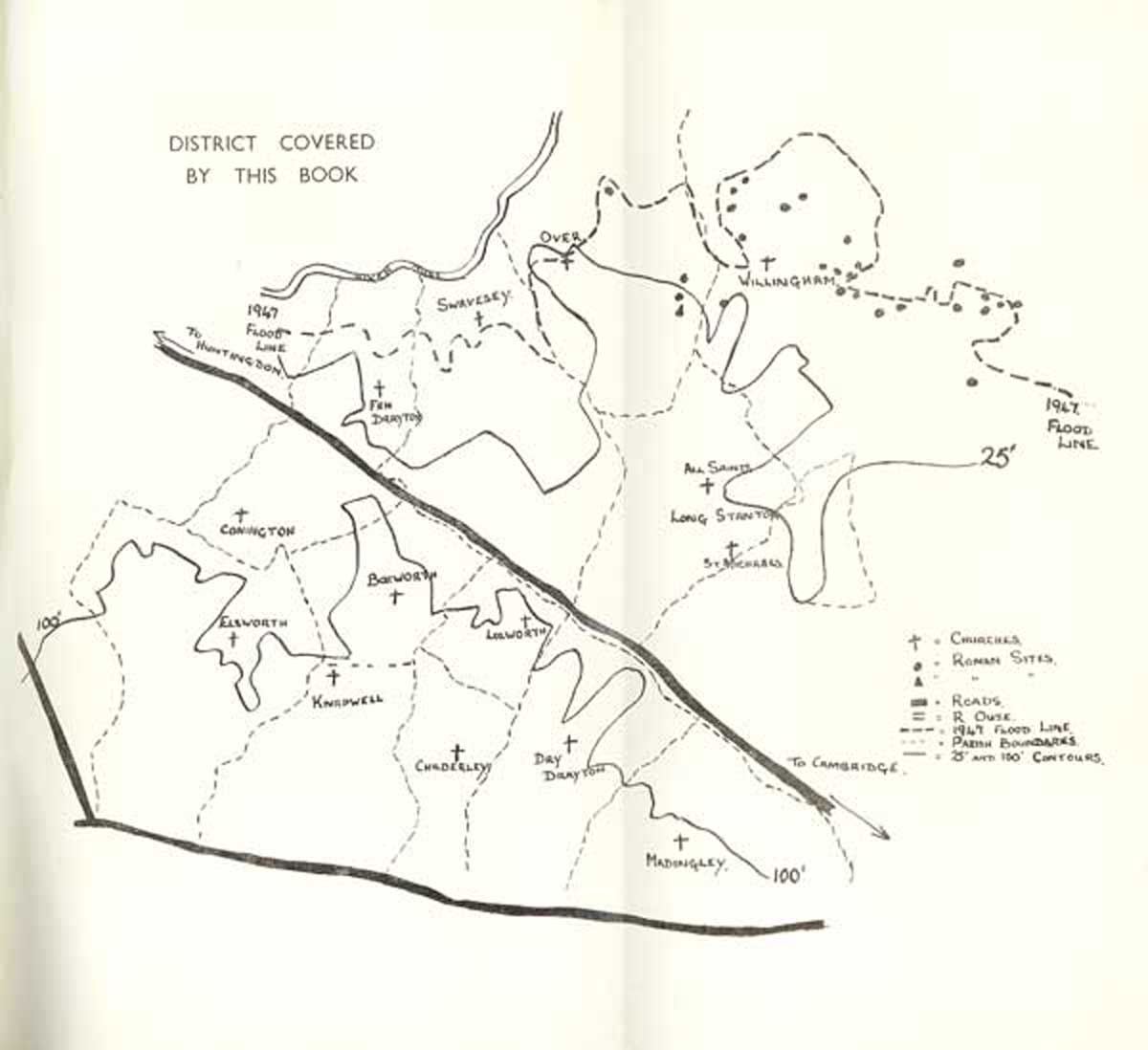

Our area rises from the bed of the Great Ouse at Over, which is only sixteen feet above sea level, to land over the 200 foot contour in the south. The Roman road from Cambridge to Huntingdon divides the area in half at about the 50 foot contour level. It is the boundary between parishes throughout the area. Those parishes which lie to the north and east of the road are low lying, fenland edge villages. Their lands are half in the fens. The floodline of 1947 (shown on the map inside back cover) revealed the older area covered by fen; much of the land on this fen edge is gravel. Contrary to common expectation there is only a small area of Peat Fen soil south of the Ouse. The area once covered by Willingham Mere is alluvial and surrounded by gravel, which stretches south to the two villages of Over and Willingham, with a narrow band going to beyond Longstanton. There is a narrow band of Ampthill clay widening out north of Papworth and forming the low ground north of Boxworth, round Longstanton, Over, and Willingham; it is bounded on the east by the lower Kimmeridge clay of Knapwell, Oakington and Willingham. This Kimmeridge clay is often overlaid with alluvial deposits. Crystals of selenite (gypsum) are often found in the Kimmeridge and Ampthill clays. Both these clays have been used for brick making. The Kimmeridge clay is also used for embanking the rivers. Deposits of Boulder Clay occur in several places on the hill tops. Associated with the former are outcrops of Elsworth Rock, a hard limestone rich in fossils.

The area covered

The numerous small streams on the northern slopes of the plateau have exposed the greensand and it is interesting to note that the villages are sited at these points, approximately 120 feet above sea level. The 100 feet contour generally marks the lower edge of the Boulder clay cap and therefore the extremity of the forested area. At Knapwell, Lolworth, Boxworth and Elsworth gravel or greensand exposures border the edge of Boulder clay and no doubt formed the principal factor in the choice of these village sites. In the whole western plateau no trace of human occupation in the prehistoric periods has been recorded. This is in direct contrast to the chalk uplands which were comparatively densely populated in Neolithic and Bronze Age Times.

The upland villages to the south of the Roman road provide a striking contrast to the villages along the Ouse bank. To the visitor from the north or west country, most of Cambridgeshire may seem strikingly flat and low-lying, but there are in fact important differences of height within the area. It is over six miles, as the crow flies, from the Ouse at Earith to the Huntingdon road by Hill Farm cottages (Swavesey); the land rises 50 feet in this six miles. From Hill cottages to Ash plantation on the St. Neots road in Knapwell parish is less than four miles, but the ground rises more than 175 feet. In fact just to the south of Hill Farm cottages, as in other places in the upland villages, the ground rises 75 feet in six hundred yards. It has been suggested that there was in early times “a stretch of high forest land on the clay from Croydon to Dry Drayton, extending across the border into Huntingdonshire”; and that this upland “clayland was once well wooded”; weald, found as a place name in the area here means ‘high forest land’. This is the view of the Place Name experts, but natural scientists have argued that the clay area would not have been capable of bearing much forest until properly drained in more recent times.

EARLY SETTLERS

At any rate the uplands in the south of the area were, before man altered them, inhospitable and inaccessible. All the evidence is that the early settlers found movement easiest by water and that the earliest human settlements were near the river Ouse and its tributary streams. Little archaeological evidence has been discovered of pre-Roman peoples living in the area, but Roman settlement seems to have been very thick on the ground. Some pre-Roman pottery has been discovered at Fen Drayton. Years of work, by Mr. John Bromwich and Mr. Michael Hopkins in Willingham parish, has revealed Roman pottery distributed in many places along two significant lines. The lower, lies just above the 1947 floodline and the other further inland just below the 25 feet contour line. Air Photography and searches in Fen Drayton and Over have shown that these two lines of Roman settlements extend all along the course of the Ouse. Perhaps the most striking find of Roman origin was the discovery of a hoard of Votive Bronzes, now in the Archaeological Museum in Downing Street, Cambridge. They were found at an unrecorded site in Willingham Fen. The most recent find in Willingham was a Lead Vat turned up by a plough in the same area in 1958. This has been repaired and is also in the Museum. The Museum also has some chains, possibly for hanging cooking pots over a fire, found at a depth of 5 feet in Over Fen. A Denarius of Faustina the elder and a great number of copper coins of the later empire (Constantine) have also been found in Over. Mr. Ernest Papworth has discovered and excavated what may prove to be a Roman pottery kiln at Coldharbour farm in Over. It is possible that an Iron Age site lies under the Roman one; more excavation remains to be done. A Roman burial was discovered four years ago near the Post Office in Fen Drayton. Last year Mrs. Matthews discovered another at the Land Settlement Association Middleton Farm. A Roman domestic site has recently been excavated in Elney Fen by the Ministry of Works.

It is now well known that the Romans developed the fens as an important grain producing area and used improved waterways to transport grain to their garrisons in the midlands and north. It seems likely that there were a whole series of farms in the clays and gravels just above the flood line. Possibly the settlement and development of the area began first on the fen edge and then moved inland and uphill in later centuries. The settlements near the water may on the other hand have been places where barges were loaded and unloaded. The building of a Roman road straight through the inhospitable waste must have made upland penetration easier. A coin of Cunobelinus (5 B.C. to 40 A.D.) was found at Childerley Gates. Two Roman coin hoards were found at Knapwell in 1840 and 1877. They include silver coins up to Marcus Auerelius’ reign and bronze coins up to Septimus Severus’ reign.

THE COMING OF THE ENGLISH

Archaeological and historical evidence for the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in the area is very small.

To interpret the arrival of the English we are driven to a study of the local place names, most of which are English in origin, and to another look at local geography. There were two ways into and through the area for new arrivals from overseas: by water and along the Roman road. Access by water was clearly the most favoured. It is no accident that the centres of Willingham, Over, Swavesey and Fen Drayton lie on or very near to tributaries of the Ouse. Swavesey gets its name from Swaef’s landing place, and Over actually means ‘bank of the river’. Until comparatively recently Swavesey was a port and boats came into the middle of the village, to what is still called Market Street. There was a wharf and dock basin here with room to turn boats or barges so that they could make the passage back to the Ouse.

Over and Needingworth, across the Ouse, were connected by a ford. Willingham gets its name as ‘the home of the people of Wifel’; the old form of the name suggests an early settlement. Fen Drayton has proved a more difficult name to explain. The Fen clearly means what it says, that the area was fenny or wet. It does not mean that the village is on peat or silt fenland soil. The Drayton comes from an old English word draeg from dragan, to draw or drag; this name usually applies to places with steep slopes up which things had to be dragged, as at Dry Drayton, or to places where boats were dragged up from the water, sometimes for portage over a narrow neck of land between water. Neither of these senses seem obviously to apply to Fen Drayton, but in fact either of them might have done so. If Drayton was an early ‘port’, as the other villages along the Ouse, boats may well have been dragged out of the water to the village site, which was safely above water level. It is equally possible that goods coming down from the upland settlements at Conington, Elsworth and Knapwell, notably timber, may have been dragged down to Drayton for sale or distribution along the Ouse waterway. Honey Hill in Fen Drayton parish is a significant name in this connection; it lies between two of the tributary streams which come down from the upland. The name is a tribute to our ancestors’ sense of humour, for it is given to especially muddy and sticky places. There is a Honeyhill wood, with the same origin, in Boxworth parish. An alternative explanation has been put forward, deriving the Dray from the old English word ‘dryge’, meaning dry. Drayton would then be the village on the dry, flood free, land nearest to the Ouse.

When we look at the upland villages two things are noticeable about them. At all times they seem to have been smaller and more scattered settlements than the larger fenland edge villages. Most of them are connected with the lowland villages by tributary streams and old trackways. Elsworth, Boxworth and Lolworth all get their names as the enclosure, or clearing in the waste or woodland, settled by an Anglo-Saxon, Eli, Bucc and Lull or Loll. Conington means ‘King or royal farm’; the first part of the name represents a Scandinavianising of an old English word. It is one of the few pieces of evidence for Danish settlement in the area. Others are Bradewonge in Boxworth, a field named from vangr, the Scandinavian for a meadow or garden; Crocdol in Long Stanton and le Croke in Swavesey, old field names from krokr, Scandinavian for a ‘crook, a bend’; and Clinthauedene in Madingley. Danish words, which remain in common use, include Skiving = lazy or idle, Frawn = frozen, Dag = heavy morning mist, Ding = a blow, Gob = mouth, Rag = teaze.

Knapwell seems to have got its name from ‘Cnapa’s spring’. It could be that Cnapa was not the name of the original settler, but simply meant boy’. In this connection Childerley, “the wood or clearing of the young men or children” is interesting. “Cild” came to be a title of honour for the sons of noble or royal families, as used in “Childe Harold”. Madingley in 1066 belonged to four sokeman; one of them was “Aelfsi cild”. ‘Cnapa’ also occurs as the name of a moneyer; it has been suggested that Knapwell gets the first part of its name from the ‘Kap’, ‘Knop’ or ‘Knot’, a large mound in a field near the church. The ‘well’ comes from the springs, underground and above ground, notably in the boundary brook. A medicinal spring, or well, containing iron, breaks out of the slope of the hill in Overhall Grove in Boxworth parish, to the east of Knapwell Church.

Madingley was ‘the wood or clearing of the people of Mada”. Long Stanton was the long “stone farm-enclosure.” The “Long”, however, is a late addition to the name. The general impression produced by the names of the villages inland from the Ouse is of isolated, remote settlements of farms and hamlets; this is confirmed by the present day topography. There is an interesting suggestion in the names of noble or royal initiative in the colonization of this waste, upland.

A water-course runs from Knapwell, Elsworth and Conington to Fen Drayton and to the river in Swavesey parish. Childerley, Lolworth and Boxworth are on streams which join the Ouse along a channel which is the parish boundary between Swavesey and Over. Buckingway road in Swavesey is an old local name, explained as ‘the track of the people of Boxworth’ or ‘Bucc’s track’; in either case it suggests a drove or track connecting upland Boxworth with the port of Swavesey. There seems little doubt, that from early times the hamlets and farms in the uplands were in communication by water and, where necessary, overland with the larger riverside settlements. It may seem strange to an age of motor cars and lorries, but it would not have seemed so to our English ancestors that movement by water should be easier than and preferred to movement along roads, even the surviving Roman roads in the area. It is most noticeable that between Cambridge and Fenstanton and between Cambridge and Eltisley no villages have grown up along the roads, though the roads are older than the villages.

DOMESDAY BOOK

In 1086 William the Conqueror took a great census of the people and the land he had conquered and of their wealth. With this Domesday Book we have for the first time documentary evidence for the history of our area. Some of the displaced Anglo-Saxons landowners are mentioned. Eddeva the Fair held land in Boxworth, Swavesey, Fen and Dry Drayton, which passed into the hands of Count Alan. Ulf, a thegn of King Edward the Confessor, held land in Fen Drayton and Swavesey ; tenants of his held land in Boxworth, Conington and Elsworth. All this land became the property of Gilbert of Gand. Other Saxons mentioned, who may have been resident landowners, were Balcuin of Madingley, Osulf and Gold of Willingham, Lefsi of Swavesey and Boxworth, Hugh at Long Stanton and Godwin at Over,

Of the forty-four tenants-in-chief, who held Cambridgeshire land from the King in 1086, sixteen held land in the area we are considering. The King, himself, only held land in Fen Drayton. The Bishop of Lincoln had land in Madingley and Childerley. The Abbey of Ely had seven hides in Willingham. The Abbey of Ramsey held land in Elsworth, Boxworth, Fen Drayton and Over, as well as the whole of Knapwell. Crowland Abbey had seven and a half hides in Dry Drayton, while the Nunnery of Chatteris held one hide in Over, worth 16s. The Church, in fact, was a substantial, perhaps the dominant, landowner in the district.

Perhaps the biggest lay landowner was Alan de Zouch, Count of Brittany. He held the main manor in Swavesey with a mill and a fishery rated at 3,750 eels annually. Monks of Swavesey Priory were the Count’s tenants for lands in Dry Drayton. Count Alan also held land in Fen Drayton, Boxworth, Willingham, and Long Stanton. Harduin de Scalers and Picot, the Norman Sheriff of Cambridgeshire, both held large areas. Harduin had land in Elsworth, Over, Conington, Boxworth and Dry Drayton, Picot in Pen Drayton, Over, Willingham, Long Stanton and Childerley, as well as the whole of Lolworth. While Knapwell and Lolworth were single manor villages, with a single owner, most of the villages had several owners and several manors.

The change brought by the Conquest was not merely one in the personnel of the tenants-in-chief, the landowners. There was a general decline in freedom. Before the Conquest there had been 144 sokemen in the area, free peasant farmers not subject to a lord; by 1086 only 39 were left. It is no accident that, of the 105 who vanished, 102 were on the estates which became Harduin’s and Picot’s. These two Norman lords had an unenviable reputation for the destruction of a free peasantry in other parts of the country as well as in our area. They carved their manors out of free peasant lands. A foreigner is recorded as living in Elsworth in 1086.

From Domesday Book we learn that there were watermills at Swavesey and Lolworth, that at Lolworth was out of use and paying nothing. As well as Count Alan’s fishery at Swavesey, Gilbert of Gand had a marsh, rated at 225 eels. There was a marsh in Long Stanton, rated at 3,200 eels, and one at Over worth 6s. 4d.; at Willingham there was a mere worth 6s. Wood for houses is recorded at Elsworth and wood for hedges at Knapwell, Lolworth, Childerley and Madingley.

With the passage of time the Church holding increased; the de Zouchs granted Swavesey and Dry Drayton land to the Priory they founded in Swavesey, as a branch of the Benedictine Abbey of Angers. Boxworth, Conington, Lolworth, Long Stanton and Madingley belonged to a succession of lay lords through the middle ages ; several families, e.g. de Boxworth of Boxworth, Elsworth of Conington, actually took their names from the villages. The de Zouchs of Swavesey alone among the lay lords of the manor were powerful locally and appropriately, had a castle in Swavesey. The rather puzzling earthworks at Castle Hill, west of the village street, seem to be the site of their Castle, but little can be learned of its nature from them. At some time during the middle ages Madingley became the shire manor it was held in trust for the county and farmed for £10 a year, which sum was used to pay the wages and expenses of the Knights of the Shire, the County’s M.P.s. In 1543 an Act of Parliament confirmed this manor to John Hynde and his heirs in return for continuation of this payment, discharging the inhabitants of Cambridgeshire of all future responsibility for the fees and wages of their M.P.s.

THE PARISH CHURCHES

The Church was present as a landlord in many of our villages, but in all of them there existed a parish church, often the only stone building in the village and the centre of its life. It is impossible in a short space to do justice to the parish churches of our area. There were no churches recorded here in Domesday Book. At Over there is a later record of a Cross near the path leading to Mill Pits and possibly there was another at Stump Corner near Willingham. Crosses were erected for open air worship in Saxon times. The first churches were usually wooden and probably such buildings existed in many of the villages. There was an Anglo-Saxon burial ground in Over near Bridge Causeway (now Chain Road). The Bishop of Ely granted a licence to build a new Church in Over in 1264, the previous church having been burnt down. Long Stanton All Saints may have had a Saxon wooden church; Elsworth church was mentioned in a grant to Ramsey Abbey of the tenth century. The only surviving evidence of Saxon stone work is in the fragments of Norman columns in Willingham church south porch, one of which is made from a Saxon grave cover, and possibly, in the open slit near the east end of Fen Drayton church.

Dating the surviving church buildings is difficult because of extensive nineteenth century restorations. Comparison of the present structures with the remarkable drawings and descriptions made by William Cole of Milton in the eighteenth century reveals that many apparently old features are really nineteenth century work. Boxworth church has Norman masonry in the south wall, however, but in most of the churches the earliest genuine work is of the early fourteenth century. Long Stanton St. Michaels is an exception, being a remarkable church of about 1230. Madingley church in the main dates from about 1300. Naturally the bigger villages had finer churches. Ely Abbey at Willingham were responsible for a magnificent church with a double hammerbeam roof; the angels were added later, during nineteenth and twentieth century restorations. Swavesey and Over churches are outstanding. An interesting feature is the common style in certain churches which suggests a common builder. Thus Dry Drayton and Swavesey churches have similar tracery in the chancels, significant when we remember that Swavesey priory was a landowner in Dry Drayton. Lolworth church has a fragment of frieze with ball-flower ornament and flowers along a tendril. An exactly similar frieze is in Over church’s south aisle, dated between 1320 and 1330. Over church has a stone bench around the inside of the outer wall; the purpose for which this was built reminds us of the proverb, ‘the weakest go to the wall’. There is a fourteenth century Sanctus bell in the church.

The churches contain many tombs and monuments too numerous to mention individually, but several are the work of outstanding sculptors. Conington has work by Grindling Gibbons in marble, There is much interesting church furniture too, fine early Tudor Chancel stalls at Elsworth, a thirteenth century chest at Long Stanton St. Michaels for example.

Parishes were initially endowed by local landlords, who retained the right to present a successor to the living when the priest died or removed. This right, the advowson, passed through many hands. At Boxworth and Lolworth the advowson has always been in the hands of laymen, the successive lords of the manor. At Dry Drayton, Elsworth and Knapwell, the advowson was in the middle ages in the hands of an abbey; Swavesey Priory in the first case, Ramsey in the other two; after the dissolution of the monasteries it passed into lay hands. The Abbot and later the Bishop of Ely had the advowson of Willingham from the beginning; he acquired that of Conington in 1282 by gift from the Elsworth who was lord of the manor. Swavesey passed from the local Priory to the Bishop at the Dissolution and later came to Jesus College, and Long Stanton All Saints came to Ely by Queen Elizabeth’s gift; it had been given by the lord of the manor to a Collegiate Church in Lincolnshire and passed to the Crown in Edward VI’s reign. The advowson of Madingley also belongs to Ely. Four Cambridge Colleges today own the advowsons of Swavesey, Fen Drayton, Long Stanton St. Michael and Over. Fen Drayton was granted to a Breton abbey, and let by them to the Priory of Swavesey; when the advowson came into the King’s hands he granted it to Christ’s College. Over belonged to Ramsey Abbey and after the Dissolution was granted by the Crown to Trinity College. Long Stanton St. Michael had a chequered career. There was a dispute about the advowson in the thirteenth century between the de Cheyney and de Colville families, a reflection of the barons’ war (see page 17). Although the King had control for a time the advowson remained in lay hands until a purchaser, Edward Lucas of London, gave it to Trinity Hall.

The Master of Trinity Hall left it in his will to Magdalene College. Clearly the quality of the local priest in each village depended in part on how the advowson was used and who by. When Trinity College obtained Over and the Bishop of Ely Long Stanton All Saints, they took the rector’s land and tithes for their own use and installed a less well paid Vicar. At Long Stanton the owner of Bar Farm was at this time made responsible for the maintenance of the Chancel roof and for the payment of £20 a year to the Vicar. Fen Drayton was served by non-resident College Fellows, who only too often failed to arrive for the Service.

DAILY LIFE IN THE MIDDLE AGES

The church and the lord of the manor dominated the life of the medieval village. Naturally they left behind them plentiful documentary records, therefore much of the space in scholarly County histories is filled with manorial and church history. Less often printed and less well known are the historical records of the daily life (and death) of the ordinary peasant. To this we thought it worth while giving some attention. On Monday June 10, 1308 Roger de Kiltone of Conington, giving evidence confirming the coming of age of John the son and heir of Simon le Havekere, stated that on the day of St. Clement (23 Nov.) 1284 he held a feast in honour of the saint, when, all his neighbours sitting to dinner, his oven and kitchen were burned. On July 16, 1311 John de Conytone gave similar evidence of the coming of age of John, son and heir of William Heved of Hardwick; he stated that he remembered the baptism of John, because on that day he lent his houses to a chaplain named William Stebrox, to hold his (the chaplain’s) feast, because he celebrated his first mass on that day; the same day the kitchen was burned.

These incidents help to bring home to us why we do not have left in our villages any medieval peasants’ houses. They were simple small one-room huts made of wood, wattle and daub or clay bat and thatch. The ‘kitchen’ was a separate building ; even the oven might be detached. Hence the impressive ‘houses’. Such structures caught fire easily and survived rarely. After all as late as 1913 Swavesey was swept by a devastating fire, in which twenty-eight old cottages perished and twenty-two families were rendered homeless. Significantly the Daily Mirror commented “Only the cottages of brick with slate roofs escaped”.

Even manorial dwellings were usually built in perishable materials and less permanent than we tend to assume. In writing of the Ancient Earth works of Cambridgeshire the Victoria County History notes ten in our area. Only two of these are in the fen edge villages — Belsar’s Hill in Willingham and Castle Hill in Swavesey. There is an important castle mound in Rampton. But there are, significantly, many more in the uplands: 3 in Boxworth, 3 in Childerley, 1 in Knapwell and 1 in Lolworth. Many of these puzzled the author of the article, but the comment, quoted about Boxworth, would seem to be the explanation of most of them. “This village was accounted the seat of the Barony of the Hobridges, or Boxworths, men of great honour and reputation in their time, who changed their names as they altered their dwellings, frequent in those times.” The sites of two of Long Stanton’s four medieval manors can be identified. Nicholas de Cheyney had a manor house at the Mound at the southern end of the village. A moat can still be seen in the wood below All Saints’ Church which probably surrounded the manor house of Ralph de Toni.

Insecurity in one’s home was probably balanced by the ease of building a new home in local materials. The general insecurity of life may have been taken for granted but it is none the less true that the threat of death was ever present, as compared with our times. Famine was not infrequent ‘the great dearth’ of 1285-8 led to many deaths from hunger and cold, recorded at Swavesey and Elsworth; significantly at Childerley thefts which occurred at this time were practically all overlooked. The famine of 1340 arose from a drought which destroyed the spring corn and peas in many parishes. The range of local crops is indicated in a table, printed in the Victoria County History, which summarizes the average acres in Dry Drayton sown annually in the C13 and C14 to various crops: wheat 40; oats: 30; peas: 13; barley: 8; maslin (mixed wheat and rye): 6; rye: 3. Between 1348-50 plague, the Black Death, attacked the inhabitants ; while the records of Elsworth show no evidence of deaths due to plague, at Dry Drayton 20 of the 42 tenants died, and presumably many more wives, children and landless men. Willingham alone seems to have increased in population in the mid-i4th century, in spite of the Black Death.

SUDDEN DEATH

Accidental death was frequent, although there were no motor cars or faulty electric wiring to kill people. At Boxworth the Court Roll records how Agnes Prat found Margery, the wife of Henry Rok, drowned by falling into a pond in her garden while cutting bushes. At Swavesey John, the ten year old son of John Walton, was getting water from a pond in John Hold’s Wineyard close; the pond was frozen and he went onto the ice with his yellow pot ; the ice broke, he fell in and was drowned. We are told that the pot was worth 1s 6d. This macabre detail was included in the contemporary record, because the pot, connected with the cause of death, became a deodand or gift to God; later such items or their cash equivalent were forfeit to the Crown. Drowning was a frequent cause of death. At Swavesey Margery and Will Ede were found drowned in a ditch in Edward I’s reign; and in the same reign it is recorded at Swavesey that Geoffrey, the son of Gilbert, fell from a boat in the Fen and was drowned. The value of the boat was meticulously recorded at 1s. and of a horse at 16s. 4d; was the boat being towed?

A domestic tragedy is recorded at Lolworth in 1353: a boy of two, playing at home, fell backwards into a pan of fermenting ale and hurt himself so badly that he died in six days the price of the pan and the ale (October, that is strong ale) was 2d. At Boxworth in 1348 a girl was accidentally killed by a horse; at Childerley in 1356, John Bond, riding an old horse, worth 3s. 4d., in the fields, fell off and broke his neck. In 1359 William the Clerk of Boxworth drove his cart with a load of dung into Boxworth field; he wished to ride on the cart on the way back. In getting up his leg caught between the cart and the horse and he fell backwards ; the horse in the cart dragged him a long way over the field and for a long time; all the while one of the horses was kicking William with his hindlegs, and so he died. The cart and horse with its harness was worth 13s. 4d. The fact that the medieval parson was also a peasant farmer is vividly brought home by this tragedy.

Sudden death was not only due to accident at work and in the home. Violence by human beings was equally common. At Swavesey in 1285 Peter de Gateway, a servant of Elene la Zouche, killed John le Parker with a knife thrust in the belly in 1299. Adam Baker killed William Andrew of Swavesey. Both these murderers took sanctuary in the parish church and then abjured the realm, surrendering their possessions, said in each case to be worth 1s. In 1336 about Christmas time a man tried to take sanctuary in Swavesey church but was headed off he killed one of his pursuers in self defence. In cases of crime the community was held responsible, for raising a hue and cry and for the deodand if the object itself could not be found. This is revealed at Knapwell in 1342. Emma la Walshaw was led by unknown robbers into Knapwell field near St. Nedestrete, robbed of her clothes, and knocked on the head with a club, worth ½d. Her throat was then cut with a knife, worth 1½d. Since the club which smashed her head and the knife that cut her throat were missing, it is difficult to know how their value was calculated! The reason for recording such a fictitious and gruesome detail is brought out by the legal decision that, since the robbers had fled, the parish of Knapwell must either produce a club and knife of the appropriate kind or pay their price, ½d. and 1½d!

Fleeing murderers frequently sought sanctuary in village churches; we have seen some Swavesey examples. Fen Drayton Church in 1260 gave sanctuary to Henry, the miller of Stanton, who, with Robert, the miller of Newsells, had killed the miller of Shepreth. Robert was caught and hanged, but Henry taking sanctuary, escaped with his life into exile. No doubt many of the peasants, to whom the village miller was anathema, as Chaucer’s tale of the Miller of Trumpington reveals, commented to the effect “When thieves fall out…. Henry incidentally forfeited 1s. for his goods; the constant repetition of 1s. suggests that the forfeiture may have become a nominal fine rather than an actual confiscation of all the criminal’s possessions. Fen Drayton gave sanctuary to two strangers in 1272 and to a male murderer and a female robber in 1280

UNUSUAL EVENTS

All this may suggest that violence was the only extraordinary event to occur in the life of a medieval villager. Two documents about coming of age and relating to Conington, to which we have already referred, give a rounded picture of unusual local events. It is improbable that in either case they all occurred on a single day as the witnesses, asked long after how they remembered a particular day, stated, but it is probable that the various events described had occurred in the village at about the time stated. In the first case Richard Golene (aged 60) recalls the baptism of John le Havekere because he had a son Robert of the same age baptized on the same day. John Kaym (50) remembers because he was godfather to John and gave him ½ mark (6s. 8d.) and a gold ring. William Quyntyn (54), who had married his wife Thephania a year earlier, buried her on 22nd Nov. and was almost mad with grief. Roger de Kiltone’s evidence we have already described (see page ii). John Pollard of Fen Drayton (40) remembers that particular November 23rd because he was robbed and almost wounded to death by the robbers. William Jek (45), also of Fen Drayton, buried his father, James, in Conington churchyard on the day John Havekere was baptized. Wymund de la Grove (58) of Elsworth states that on the day in question he caused to be read before the parishioners of Conington the charters of a parcel of land which he bought there ; he took seisin on the same day and was ejected on the morrow. Robert de la Brok of Elsworth, William Fraunkeleyn of Boxworth, William Morel of Fen Drayton, John Pount and William de la Grove of Swavesey (all 50 or older), caused their staves and purses to he consecrated in Conington church on Nov. 24th 1284 and began a journey to St. Andrews in Scotland.

The second collection of evidence was made on 16 July 1311 to prove the coming of age of John Heved of Herdewyk. Geoffrey (46), John’s godfather, stated that John was twenty-one on 21 March 1311 for he was born in Conington on that day in 1289 and baptized the next day John would actually seem to have been 22! William Hampt (50) remembers the baptism because his next door neighbour William Golene died and was buried at that time. William, the Clerk of Conington (60+ ), buried his father on 20 March 1289. Richard Gokne (48 +) made his homage on 21st March ; presumably he was taking over his father, William’s holding of land in the manor. John Kaym (43+) married his sister, Elice, on this day, to John, brother of the rector of Conington; Kaym, with another named Henry, led her to the church and back. William Quyntyn (now described as 52+ three years earlier in 1308 he was 54!) remembers his wife’s sad death, but now states that it occurred on May 28, 1290; in 1308 he had stated that she was buried on 22 Nov. 1284. This is interesting confirmation that the events, so glibly described as all occurring on one day, were probably in fact the local sensations of several years. Quyntyn goes on to add a further detail, that he was excommunicated by the rector in the church for selling an ox on St. Benet’s day (21 March). Bartholomew de Glemesford (50+) remembers the baptism because his own son, John, was baptized on the same day in the same water. Wymund de la Grove (70+), on March 21st, married one Isabel and William Heved, John’s father, was at his house at a feast and told him of the birth of John. William More (80) remembers the day because his son, Henry, on that day set out on a pilgrimage to Rome and never returned. Robert Stebrox (60+) remembers the day because it was the day his son William celebrated his first Mass in Conington and baptized John. William Habraham (44+) says that on this day his mother Margaret gave him an acre of land in Fen Drayton and on the next day (22 March) he caused the charter to be read. There was a celebration of a new Mass at Conington and after it he saw John Heved baptized. John de Conington (41+) then describes how he lost his kitchen due to lending it to the priest for the feast to celebrate his first Mass. These two surviving accounts give us, incidentally, a vivid picture of the kind of events which seemed memorable to local villagers in the late thirteenth century.

BATTLE

Battle, like murder and sudden death, disturbed the routine of medieval life. The isle of Ely was a refuge for rebels and for the defeated for many centuries. Danish invaders followed the Anglo-Saxon settlers. It is our private suspicion that Belsar’s Hill in Willingham may prove, when excavated, to be a Danish military camp, rather than the Norman or Bronze Age site it is often believed to be. Its site in relation to the Ouse and its shape is reminiscent of Trelleborg in Denmark. The driftway is supposed to have been in use since Norman times; it was the principal line of approach to Ely. On the 1836 ordnance survey map it is shown passing round the site on the east side; so the camp site should be older. Hereward’s resistance to the Norman conquest centred on Ely; much of the fighting took place to the south and east of our area, but, if William’s main attack around Alrehede was at Aldreth as one interpretation has it, clearly Willingham and probably many neighbouring villages must have seen much Norman coming and going. During Stephen’s reign (1134-54) civil war again centred on the Isle of Ely.

The civil war, which raged between Henry III and the barons led by Simon de Montfort, left its mark in the neighbourhood. Simon himself seized Henry de Nafford’s Long Stanton manor after his victory at Lewes. The incumbent of Long Stanton St. Michael, a nominee of one of Simon’s followers, Phillip de Colville, followed his betters’ example with an attack on William de Cheyney’s manor. After the King’s victory at Evesham his supporters retaliated: Alan la Zouch of Swavesey seized Thomas de Elsworth’s lands in Swavesey and Conington. The disinherited members of the baronial party fled to Ely in 1266 and made the island once again a centre of resistance. They raided and plundered for food in the surrounding countryside, concentrating on the lands of the church and those of royal supporters; Crowland abbey lands and buildings and the parish church at Willingham were attacked, as were the conventual buildings of Swavesey priory. No doubt an attack like this explains the grant of free corn obtained by Alan la Zouch in 1267, because his corn at Swavesey had been burned by the King’s enemies. In the same year Simon of Swavesey needed a safe conduct to go to the King’s Court.

TAXATION AND THE PEASANTS’ REVOLT

Royal taxation on top of manorial dues can never have been popular. This was usually presented as taxation for war. In 1316, for example, Cambridgeshire villages had to raise money for the Scottish war. 19s 4d was raised from the village of Fen Drayton, an average of 8d. from each taxable person; 6s 8d of this money was used to buy one aketon with bacinct. For the Lay Subsidy of 1327 £7 13s 9d was raised from 546 people of Over, £9 3s 2d from 576 people of Swavesey, £5 6s 8d from 258 people of Willingharn, £1 10s from 162 people of Fen Drayton, and £1 8s 7½d from Knapwell. The highest sums paid in each village varied from 2s 9d in Knapwell to 12s in Swavesey. The differences clearly represented differences of wealth among the taxpayers, but the tax may well have fallen unequally as between villages and individuals. In 1377 the 111 adults of Fen Drayton paid £1 17s towards the Poll tax. There were four local collectors John Boleyne and John Beton, the Constables, and William Maddy and William Abraham, additional sub-collectors.

In 1381 the peasantry over much of southern and eastern England rose in revolt against the Poll Tax and various oppressions by their lords. In many places church landlords were particularly attacked. Dr. Palmer states that there were no attacks on the Ramsey manors in Elsworth, Over and elsewhere, but throughout the months after the revolt was put down the Abbey of Ramsey was issuing commands that its peasants should perform their traditional services, so there must have been some discontent. John Cook led a band of peasants north to attack Thomas de Elsworth’s property at Elsworth, and John Scot of Milton came with a band to Lolworth to the house of John Sigar, threatening his wife Mabel that they would pull down her houses unless Sigar granted them freehold possession of lands in Girton and Madingley. William la Zouch of Swavesey headed the judicial commission which put down the revolt with a short reign of terror. William de Cheyne of Long Stanton sat on the Commission. Swavesey had had its own troubles, though it is not clear whether revolt in the village was spontaneous or due to John Cook’s arrival. Fen Drayton rising was also attributed to John Cook, who was outlawed on June 15th 1381 and his land (50 acres) and goods worth £6 7s 6d confiscated.

PROPERTY RIGHTS AND DUES

Everyday life ought obviously to bulk larger than the sensational if our account is to be true to life, but we are faced with the difficulty of either repeating what is common to every book on medieval peasant life or writing a history of each village, which is not our intention. There is only space for a few hints. Land in these agricultural communities was much subdivided and sublet, and so one finds a virgate (the typical 30/40 acre peasant holding) in Knapwell in 1255 in which many people have some right or other. The details are difficult to sort out. The virgate had descended to one William de Schelford who was hanged in London on 11 July for murdering his father. The King’s claim, presumably because of the murder, was valued at 6s. 4d. saving the corn crop from ten acres already taken from the executors of John de Schelford who had been killed. The virgate was held of William Burred for a yearly payment of a pound of cummin and 1s made to the heirs of Henry le Eveske, lord of the fee. But one Emma held three acres and a house belonging to the virgate, for which she paid 3s to the heirs of Nicholas de Vavasour and to Silurius Lenveise the remainder to the virgate which was worth 15s was described as held of the same heirs. The Schelfords and Emma seem to have been the actual farming tenants.

The Prior at Swavesey owned property there and in Dry Drayton; from quite a different aspect his property reveals equally clearly the complex obligations of ownership in the medieval village. In 1279 he held the Rectory of Swavesey in his own right and two virgates of Lady Eleanor la Zouch, paying her 8s a year to hold his own manor court and to survey his tenants’ gallon and bushel measures; these had still to be presented twice yearly in Lady Eleanor’s court. The Prior also had a fishery, a weir and a fishhouse in the Ouse. In 1285 he was in trouble for overstocking his Dry Drayton farm. He owned one hide in the parish and his stint of the pasturage was six oxen, two horses, six cows, eighty sheep and thirteen geese. He had in fact a flock of six hundred sheep and a herd of one hundred and twenty mixed cattle. There survives from the late fifteenth century a record of the Prior’s annual expenses and payments.

| £ s. d. | |

| For the farm of the parsonage of Swavesey and for the rent of Dry Drayton, payable on Feb. 2 and Sep. 14 | 37 0 0 |

| Also in yearly distributions in the parish at the feast of St. Andrew as much bread as is made of a quarter of good wheat and a ‘Mays’ (a measure) of red herrings in alms to the poor. | |

| Item he gives two acres of marshland to the farmer of Dry Drayton to the repair of the walls. | |

| Item he payeth yearly to the Bishop of Ely | 13 4 |

| Item he payeth to the Archdeacon | 6 8 |

| Item to the prior of Ely | 10 0 |

| Item to lord of Swavesey | 8 0 |

| Item to the Collector of Brytonmesses (that is the Steward of Zouch of Brittany’s manor) for Dry Drayton | 2 0 |

| Item to the proctor of his fee for answering at the Visitations and Sene (synod) | 3 4 |

| Item for the decay of a tenement at the Cross | 3 4 |

This was the Benedictine priory founded by Alan de Zouch in William I’s reign, which in 1393 was transferred to the Charterhouse at Coventry. The mixture of ecclesiastical obligations to superiors and inferiors with rental obligations to land-lords and the equivalent of local taxes is typical of the obligations which went with property ownership in the middle ages. A layman would have had fewer ecclesiastical payments to make and a peasant altogether less to pay, but the same mixture would have been present.

The obligations of peasant tenants to their landlords varied. The Victoria County History suggests that “the conditions of villein tenure were considerably lighter on manors in lay hands than they were on those held by the Church.” On Ely manors— and Ely had a manor in Willingham and land in Over—the villein (serf) tenants had to work on the church’s demesne (home farm) land for “three days a week, before Whitsun from morning till nones, and after Whitsun until vespers, ‘and note that no allowance shall be made for any festival in the year except the day of Christmas’”. While “On the Zouche manor of Swavesey in 1275 the custom was for 31 villeins to work one year and the other 32 next year, paying 8d. rent when working and 2s. 10d. when not.” “When all the services of the villeins were not required on one manor they were sometimes sent to another ; thus at Dry Drayton in 1822, 104 ‘works’ were received from Oakington and 169 from Cottenham, and in 1327 the Abbot of Ramsey’s tenants at Knapwell did 38 of their works on his manor of Elsworth.” Dry Drayton, Oakington and Cottenham were manors of the abbey of Crowland, and they shared one manorial court. In 1310 Giles de Hyngeston of Over, according to Mrs. Bold’s history of the village, took works and rent from some of his tenants but only rent from others. While Henri Koe owed l0d and 2 capons a year, John Reynold paid “3s. 2d. and 2 capons, and one man to work for two days (a week) and one man two days in August and one man to flail at Michaelmas one day”. In addition “all the homages (owed) wast pennies and the service of each householder one man one day to make my hay”.

The Church, as landlord, was stricter than the layman; the peasant, who was personally free, was normally less burdened than the serf. But sometimes, and especially when the Church was his landlord, even the freeman had onerous obligations. Ely’s free tenants had to send their men to work on the boonday. At Willingham “Thomas Something (Aliquid or Aucunchose!) who held a quarter knight’s fee, ‘shall himself ride with them to see that they work well’ “. “More remarkable is the fact that on many of the Ely manors (Willingham) free tenants paid heriot, leyrwite, and a fine (gersuman) for marrying their daughters, such renders being usually considered typical of villein status.” The Church was not always stricter than the lay landlord. For at Dry Drayton, as on the other Crowland manors, “some provision for the aged and infirm was made, until the middle of the 14th century”, while elsewhere “when a villein became incapable he had to give up his holding. Widows, however, retained their husband’s holdings as ‘free bench’, and on the Ely manors (Willingham) it was the custom that when a villein died from whom a heriot of the best beast was due, his widow should have the use of the beast for 30 days ‘to the support of her waynage and should be excused her work-dues

AGRICULTURE

The village arable lands were unhedged and divided in allotment like strips, each tenant’s strips being scattered. The rotation of crops was a communal matter. A similar system was operated in the early days of the Land Settlement at Fen Drayton; a crop for example, potatoes, would be sown in one field, irrespective of the holding boundaries and each tenant was expected to do certain work on the crop at specified times. At Willingham and Madingley the village fields were divided into three blocks, following a rotation of spring crops, autumn crops, fallow. At Boxworth and Elsworth apparently a two-field division existed. The crops grown in Dry Drayton’s fields have been described on page 12. In the fen edge villages there were many additional special crops sedge was cut at four yearly intervals for thatching, kindling and litter. Teazles were grown at Over for dressing wool cloth. Woad was grown in Over and Swavesey from the 10th century mostly on the south and southwest side of Over town. It was marketed in Swavesey and taken across the river to Slepe (St. Ives) Market. From St. Ives this beautiful blue dye was exported to the Continent.

Animal husbandry played an important part in the village economy, not least because of the value of the manure. “At Long Stanton if a villein had sheep of his own or of his family he had to take them to the manor-house, with his own hurdles, from Michaelmas to Christmas”. This was so that the lord could get the benefit of the manure on his land. Owing to the variations of soil in the area, the animal stock varied from parish to parish. ‘Thus on the three Crowland manors, between 1258 and 1315, – only Dry Drayton, on the chalk, had sheep, numbering between 120 and 350 – for the demesne”. In addition “the tenant of every hide (140 acres at Dry Drayton) had the right to graze on the commons 6 oxen, 2 horses, 6 cows, 80 sheep and 15 geese.” We have seen how in 1285 the Prior of Swavesey, who was a tenant of one hide in Dry Drayton, had 120 cattle and 600 sheep on the commons, Others followed his example, so Dry Drayton must have had a large sheep population. The Ely demesne in Willingham in 1277 supported 16 cows (20 in a dry season), 2 bulls, 20 pigs, 1 boar, and 240 sheep. The fenland edge villages had a further local asset, their fisheries; in 1277 there was on Willingham mere an open-water fishery for three boats, paying the Ely landlord 30s each. The farming possibilities of the fen edge villages were well summed up in a survey of Over Manor, made in 1575 ‘a reasonable good soile for corn and grass, yet very barron of wood and timber. And the pasture and meadow grounds being mares and fenns be for the most parte in the winter time surrounded with water. And wett partely by soak of the fens lying so near the great River and partly by rain and water.” Of Housefen the Survey stated that it “hath ever been time out of minde the fen wherein the inhabitants of Over have been accustomed to get fodder for the keeping of their cattle in wintertime – after the first crop or so much thereof taken as the seasen of the year for wetness and drought will suffer which is many times uncertain the said inhabitants have accustomed to spare it till the feast of St. Peter (commonly called Lamas Day) (1 Aug.) or St. Michael th’ archangel at the discretion of the Fen greeves and from thence is fed off with cattle of the inhabitants sans nombre, hoggs, geese and sheep only excepted till it be spared for hay next year”.

Barefen, Langdridge and Skeggs “have time out of memory of man been Easter Common to the tenants of Over and Willingham for all manner of cattle sans nombre – in good dry years there was more grass than was needed”. The assets of living near the fens was balanced by an extra duty, “the compulsion on a large proportion of the bishop’s tenants to work on the causeway of Aldreth (which runs through Willingham parish), which formed the land approach to Ely, or to pay pontage in lieu of such work”. The affairs of each manor were managed by a local reeve, “the executive officer, who supervised the actual working of the farm and kept the accounts”. The reeve might hold office for long periods “at Dry Drayton the same reeve seems to have served for 30 years”. The 1279 Hundred Rolls informs us that the Abbot of Ramsey had a Gallows in Elsworth, Knapwell and Graveley and held a court there.

MARKETS AND FAIRS

The medieval village had to exchange its goods and, therefore, an annual fair and weekly markets were prized rights. On July 26 1244 Alan la Zouche and his heirs were granted the right to hold a weekly market in Swavesey on Tuesdays, and a yearly fair on the vigil, feast and morrow of the Holy Trinity. In 1261 the Swavesey fair was altered to St. Michael’s day and the five days following (29 Sep. to 4 Oct. inclusive); in 1505 the fair was moved to Trinity Sunday again. Swavesey acquired in the early middle ages something of the status of a market town. From the Hundred Rolls of 1279 we learn that there were several burgesses in the village, paying rents of between 2s 6d and 5s a year. They included Henry the Smith, John the Barber and John Medic (the doctor), as well as several people with surnames. Over Market was in the rectangle by the Rectory and near the Guildhall; there has been no market held within living memory. It is possible that Elsworth and Knapwell marketed their produce at Caxton which lies on the old north road.

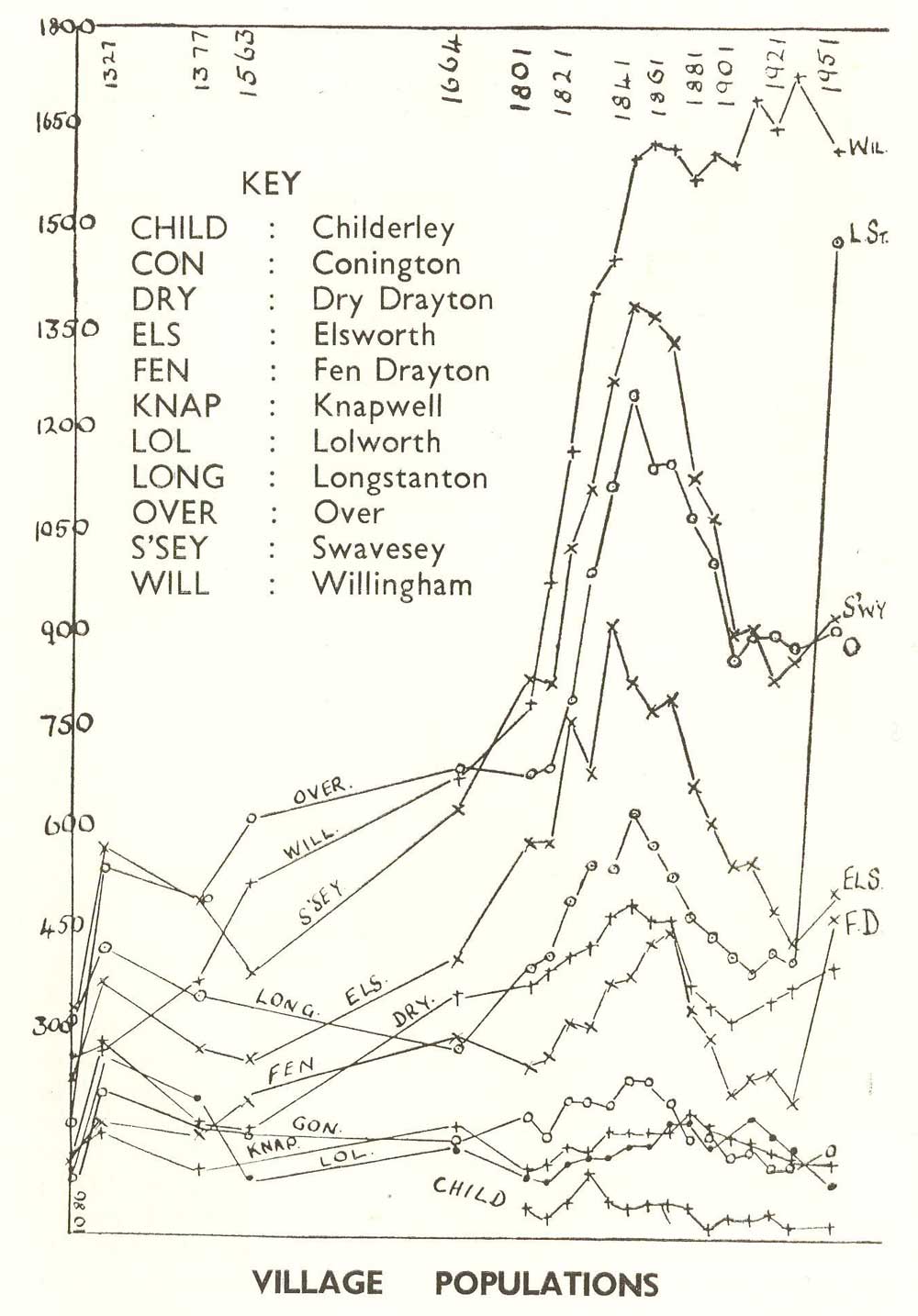

POPULATION CHANGES

This graph shows what happened to the population in each village in our area from Domesday Book to this century. The changes in population provide a summary reminder of the medieval history which we have been looking at and a foretaste of the following centuries. Between 1086 (Domesday Book) and 1327, the date of the Subsidy Roll from which our next figure is taken, all the villages increased in population. Over, and to a less extent Swavesey, increased in size far faster than the other villages, to become outstandingly the largest communities. Over increased its population by three and a half times. The next figure is from the Poll Tax of 1377; between 1327 and this date, bubonic plague entered England the Black Death of 1348/9 was followed by lesser outbreaks. It is not surprising that every village bar one had fallen in population between 1327 and 1377. Willingham was the great exception its population had increased by nearly 50% when many of the villages had shrunk by between one third and one fifth. The next return is that made to the Bishop in 1563. There is no return available for Knapwell and Long Stanton. But the rest of the villages had differing experiences in the two hundred years from 1377 to 1563. Over, Willingham and Fen Drayton increased their population considerably; Willingham became the second largest village in the area, not much smaller than Over. The upland villages did not share in this rise of population Conington, Dry Drayton and Elsworth remained static in population, while Lolworth and Boxworth seem to have fallen. The surprising figure in the return is that for Swavesey, which suggests a population drop of nearly 30%. Since the next return available one hundred years later shows that Swavesey’s population had increased over the 1563 figure at a faster rate than any other village, it is possible that in fact the return of 1563 for Swavesey is wrong. Perhaps the parson, making it, underestimated the size of his congregations.

The Hearth Tax return of 1664 shows a general tendency for population to increase; Willingham has almost overtaken Over and Swavesey is not far behind; Dry Drayton, Elsworth and Fen Drayton all had a big increase; but Conington and Long Stanton dropped in population. When the first government Census was taken in 1801, Swavesey was the most populated village in the area, and Willingham close behind with nearly 800 inhabitants; Over had only 700. Elsworth was the next largest with 580 people, much the most populous upland parish while Lolworth and Knapwell had the smallest populations, about 100 people each. The next fifty or sixty years saw a rapid population rise in every village, which was followed by an equally sharp fall until well into the twentieth century. These changes in population bring out very clearly the different history, in general of the upland and the fenland parishes. In 1911 Boxworth, Conington, Dry Drayton, Knapwell and Lolworth were not much more populated than they had been at the time of Domesday Book ; Elsworth alone had grown considerably ; its population was between two and three times that of Domesday Book. Of the fenland edge villages Long Stanton had grown least, by a quarter; but Fen Drayton and Swavesey were about three times as big, Over nearly six times and Willingham about twenty times as populous as in Domesday Book.