FEN & UPLAND

2000 Years of History

Swavesey Village College, 1961

Photo: Cambridge Daily News.

The information in this document was written and

published by a small team of amateur historians in conjunction with Swavesey

Village College in 1961

The booklet was loaned by Mr. Christopher Rule whose

father was one of the original contributors. It was scanned and formatted by

Jon Edney in 2005.

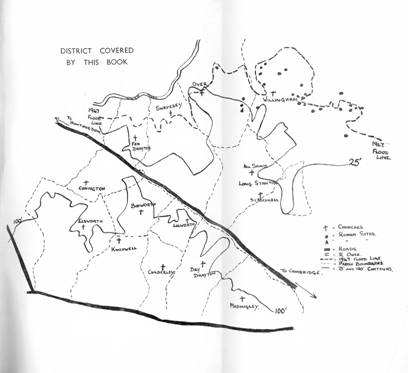

PREFACE

In this booklet we have

tried to put before the people, who live in the villages served by Swavesey

Village College, an introduction to the history of their neighbourhood. We deal

with the area of Cambridgeshire which lies between the Ouse river

and the old road from Cambridge to St. Neots. To the

west the area reaches as far as the parishes of Fen Drayton and Elsworth and to

the east as far as Willingham, Long Stanton and Madingley. The area lies close

to the O~ meridian, on which Swavesey station lies. Many of the villages in

this area deserve a full history of their own ; this

booklet is no substitute for such histories ; indeed, we hope that the work

which has gone into producing it and the sale which we hope it will get in the

area may stimulate the production of several separate village histories.

The authors of this historical

study were students in a three year Tutorial Class in Local History, held in

the Village College, Swavesey, between 1958 and 1961 under the auspices of the

University of Cambridge Board of Extramural Studies.

Mr. Lionel Munby, M.A., was Tutor to the class and

has edited the material collected by the students. We should like to thank Dr.

M. H. Clifford, Dr. Audrey Ozanne, Mr. Humphrey

Bash-ford, and Dr. Esther Dc Waal ; without the

stimulus which their teaching brought we should not have attempted even such an

elementary study as this is. Many other people have helped us with information

and advice; it would be impossible to name them all. But we should like to

thank, in particular, the clergy of the parishes we deal with, Miss Claire

Cross, the County

Archivist,

and Miss H. Margaret Clark, to whose researches we owe the study of Long

Stanton in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Some of the contents of this booklet are the

product of research on original documents and into topographical and archaeological

material. Much of our matter is culled from material already published, notably

the Victoria County History, as will be obvious to those who already know

something of our local history. But this work is not primarily intended for

them. We hope in it to bring to many local people, who have not previously

studied the history of their village, something of the interest we have gained

during the last three years.

Our publication would have

been impossible without the generosity and faith of many people, to whom, as to

the County Education Committee and the Students Council of the Village College,

we owe a debt for financial assistance. It is our hope that wide sales of our

work will enable us rapidly to repay their loans.

NAMES OF CLASS MEMBERS

Mrs. Banks. Mr. R. Palmer.

Mrs. B. Duff. Mrs. R. Palmer.

Mr. B. Duff. Mr. E. Papworth.

Mrs. E. Ford. The Rev.

R. Pearson.

Mr. M. Hopkins. Mrs. R. Pearson.

Mr. A. Hunter. Mr. R. Rule.

Mr. A. Houshan. Mrs. J. Stroud.

Miss Kennett. Mr. D. Williams.

Mrs. D. Matthews.

PART ONE

TO THE END OF THE MIDDLE AGES

THE AREA

Our area rises from the bed

of the Great Ouse at Over, which is only sixteen feet

above sea level, to land over the 200 foot contour in the south. The Roman road

from Cambridge to Huntingdon divides the area in half at about the 50 foot

contour level. It is the boundary between parishes throughout the area. Those

parishes which lie to the north and east of the road are low lying, fenland

edge villages. Their lands are half in the fens. The floodline

of 1947 (shown on the map inside back cover) revealed the older area covered by

fen; much of the land on this fen edge is gravel. Contrary to common

expectation there is only a small area of Peat Fen soil south of the Ouse. The

area once covered by Willingham Mere is alluvial and surrounded by gravel,

which stretches south to the two villages of Over and Willingham, with a narrow

band going to beyond Longstanton. There is a narrow

band of Ampthill clay widening out north of Papworth and forming the low ground north of Boxworth,

round Longstanton, Over, and Willingham; it is

bounded on the east by the lower Kimmeridge clay of

Knapwell, Oakington and Willingham. This Kimmeridge

clay is often overlaid with alluvial deposits. Crystals of selenite

(gypsum) are often found in the Kimmeridge and Ampthill clays. Both these clays have been used for brick

making. The Kimmeridge clay is also used for embanking

the rivers. Deposits of Boulder Clay occur in several places on the hill tops.

Associated with the former are outcrops of Elsworth Rock, a hard limestone rich

in fossils. The numerous small streams on the northern slopes of the plateau

have exposed the greensand and it is interesting to note that the villages are

sited at these points, approximately 120 feet above sea level. The 100 feet

contour generally marks the lower edge of the Boulder clay cap and therefore

the extremity of the forested area. At Knapwell, Lolworth, Boxworth and

Elsworth gravel or greensand exposures border the edge of Boulder clay and no

doubt formed the principal factor in the choice of these village sites. In the

whole western plateau no trace of human occupation in the prehistoric periods

has been recorded. This is in direct contrast to the chalk uplands which were

comparatively densely populated in Neolithic and Bronze Age Times.

The upland villages to the

south of the Roman road provide a striking contrast to the villages along the

Ouse bank. To the visitor from the north or west country,

most of Cambridgeshire may seem strikingly flat and low-lying, but there are in

fact important differences of height within the area. It is over six miles, as

the crow flies, from the Ouse at Earith to the

Huntingdon road by Hill Farm cottages (Swavesey); the land rises 50 feet in

this six miles. From Hill cottages to Ash plantation on the St. Neots road in Knapwell parish is less than four miles, but

the ground rises more than 175 feet. In fact just to the south of Hill Farm

cottages, as in other places in the upland villages, the ground rises 75 feet

in six hundred yards. It has been suggested that there was in early times “a

stretch of high forest land on the clay from Croydon

to Dry Drayton, extending across the border into Huntingdonshire”; and that

this upland “clayland was once well wooded”; weald,

found as a place name in the area here means ‘high forest land’. This is the

view of the Place Name experts, but natural scientists have argued that the

clay area would not have been capable of bearing much forest until properly

drained in more recent times.

EARLY SETTLERS

At any rate the uplands in

the south of the area were, before man altered them, inhospitable and

inaccessible. All the evidence is that the early settlers found movement

easiest by water and that the earliest human settlements were near the river

Ouse and its tributary streams. Little archaeological evidence has been

discovered of pre-Roman peoples living in the area, but Roman settlement seems

to have been very thick on the ground. Some pre-Roman pottery has been

discovered at Fen Drayton. Years of work, by Mr. John Bromwich and Mr. Michael

Hopkins in Willingham parish, has revealed Roman

pottery distributed in many places along two significant lines. The lower, lies

just above the 1947 floodline and the other further

inland just below the 25 feet contour line. Air Photography and searches in Fen

Drayton and Over have shown that these two lines of

Roman settlements extend all along the course of the Ouse. Perhaps the most

striking find of Roman origin was the discovery of a hoard of Votive Bronzes,

now in the Archaeological Museum in Downing Street, Cambridge. They were found

at an unrecorded site in Willingham Fen. The most recent find in Willingham was

a Lead Vat turned up by a plough in the same area in 1958. This has been

repaired and is also in the Museum. The Museum also has some chains, possibly

for hanging cooking pots over a fire, found at a depth of 5 feet in Over Fen. A

Denarius of Faustina the elder and a great number of

copper coins of the later empire (Constantine) have also been found in Over. Mr. Ernest Papworth has discovered and

excavated what may prove to be a Roman pottery kiln at Coldharbour

farm in Over. It is possible that an Iron Age site lies under the Roman

one; more excavation remains to be done. A Roman burial was discovered four

years ago near the Post Office in Fen Drayton. Last year Mrs. Matthews

discovered another at the Land Settlement Association Middleton Farm. A Roman

domestic site has recently been excavated in Elney

Fen by the Ministry of Works.

It is now well known that

the Romans developed the fens as an important grain producing area and used

improved waterways to transport grain to their garrisons in the midlands and

north. It seems likely that there were a whole series of farms in the clays and

gravels just above the flood line. Possibly the settlement and development of

the area began first on the fen edge and then moved inland and uphill in later

centuries. The settlements near the water may on the other hand have been

places where barges were loaded and unloaded. The building of a Roman road

straight through the inhospitable waste must have made upland penetration

easier. A coin of Cunobelinus (5 B.C. to 40 A.D.) was

found at Childerley Gates. Two Roman coin hoards were found at Knapwell in 1840

and 1877. They include silver coins up to Marcus Auerelius’

reign and bronze coins up to Septimus Severus’ reign.

THE COMING OF THE ENGLISH

Archaeological and

historical evidence for the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in the area is very

small.

To interpret the arrival of

the English we are driven to a study of the local place names, most of which

are English in origin, and to another look at local geography. There were two

ways into and through the area for new arrivals from overseas: by water and

along the Roman road. Access by water was clearly the most favoured. It is no

accident that the centres of Willingham, Over, Swavesey and Fen Drayton lie on or very near to tributaries of the Ouse. Swavesey

gets its name from Swaef’s landing place, and Over actually means ‘bank of the river’. Until comparatively

recently Swavesey was a port and boats came into the middle of the village, to

what is still called Market Street. There was a wharf and dock basin here with

room to turn boats or barges so that they could make the passage back to the

Ouse.

Over and Needingworth, across the Ouse, were connected by a ford.

Willingham gets its name as ‘the home of the people of Wifel’;

the old form of the name suggests an early settlement. Fen Drayton has proved a

more difficult name to explain. The Fen clearly means what it says, that the

area was fenny or wet. It does not mean that the village is on peat or silt

fenland soil. The Drayton comes from an old English word draeg

from dragan, to draw or drag; this name usually

applies to places with steep slopes up which things had to be dragged, as at

Dry Drayton, or to places where boats were dragged up from the water, sometimes

for portage over a narrow neck of land between water. Neither of these senses

seem obviously to apply to Fen Drayton, but in fact either of them might have

done so. If Drayton was an early ‘port’, as the other villages along the Ouse,

boats may well have been dragged out of the water to the village site, which

was safely above water level. It is equally possible that goods coming down

from the upland settlements at Conington, Elsworth and Knapwell, notably

timber, may have been dragged down to Drayton for sale or distribution along

the Ouse waterway. Honey Hill in Fen Drayton parish is a significant name in

this connection; it lies between two of the tributary streams which come down

from the upland. The name is a tribute to our ancestors’ sense of humour, for

it is given to especially muddy and sticky places. There is a Honeyhill wood, with the same origin, in Boxworth parish.

An alternative explanation has been put forward, deriving the Dray from the old

English word ‘dryge’, meaning dry. Drayton would then

be the village on the dry, flood free, land nearest to the Ouse.

When we look at the upland

villages two things are noticeable about them. At all times they seem to have

been smaller and more scattered settlements than the larger fenland edge

villages. Most of them are connected with the lowland villages by tributary

streams and old trackways. Elsworth, Boxworth and

Lolworth all get their names as the enclosure, or clearing in the waste or

woodland, settled by an Anglo-Saxon, Eli, Bucc and

Lull or Loll. Conington means ‘King or royal farm’; the first part of the name

represents a Scandinavianising of an old English

word. It is one of the few pieces of evidence for Danish settlement in the

area. Others are Bradewonge in Boxworth, a field

named from vangr, the Scandinavian for a meadow or

garden; Crocdol in Long Stanton and le Croke in Swavesey, old field names from krokr,

Scandinavian for a ‘crook, a bend’; and Clinthauedene

in Madingley. Danish words, which remain in common use, include Skiving = lazy

or idle, Frawn = frozen, Dag = heavy morning mist,

Ding = a blow, Gob = mouth, Rag = teaze.

Knapwell seems to have got

its name from ‘Cnapa’s spring’. It could be that Cnapa was not the name of the original settler, but simply

meant boy’. In this connection Childerley, “the wood or clearing of the young

men or children” is interesting. “Cild” came to be a

title of honour for the sons of noble or royal families, as used in “Childe

Harold”. Madingley in 1066 belonged to four sokeman;

one of them was “Aelfsi cild”.

‘Cnapa’ also occurs as the name of a moneyer; it has been suggested that Knapwell gets the first

part of its name from the ‘Kap’, ‘Knop’

or ‘Knot’, a large mound in a field near the church. The ‘well’ comes from the

springs, underground and above ground, notably in the boundary brook. A

medicinal spring, or well, containing iron, breaks out of the slope of the hill

in Overhall Grove in Boxworth parish, to the east of

Knapwell Church.

Madingley was ‘the wood or

clearing of the people of Mada”. Long Stanton was the

long “stone farm-enclosure.” The “Long”, however, is a late addition to the

name. The general impression produced by the names of the villages inland from

the Ouse is of isolated, remote settlements of farms and hamlets; this is

confirmed by the present day topography. There is an interesting suggestion in

the names of noble or royal initiative in the colonization of this waste,

upland.

A water-course runs from

Knapwell, Elsworth and Conington to Fen Drayton and to the river in Swavesey

parish. Childerley, Lolworth and Boxworth are on streams which join the Ouse

along a channel which is the parish boundary between Swavesey and Over. Buckingway road in Swavesey is an old local name,

explained as ‘the track of the people of Boxworth’ or ‘Bucc’s

track’; in either case it suggests a drove or track connecting upland Boxworth

with the port of Swavesey. There seems little doubt, that from early times the

hamlets and farms in the uplands were in communication by water and, where

necessary, overland with the larger riverside settlements. It may seem strange

to an age of motor cars and lorries, but it would not

have seemed so to our English ancestors that movement by water should be easier

than and preferred to movement along roads, even the surviving Roman roads in

the area. It is most noticeable that between Cambridge and Fenstanton and

between Cambridge and Eltisley no villages have grown up along the roads,

though the roads are older than the villages.

DOMESDAY BOOK

In 1086 William the

Conqueror took a great census of the people and the land he had conquered and

of their wealth. With this Domesday Book we have for the first time documentary

evidence for the history of our area. Some of the displaced Anglo-Saxons

landowners are mentioned. Eddeva the Fair held land

in Boxworth, Swavesey, Fen and Dry Drayton, which passed into the hands of

Count Alan. Ulf, a thegn of King Edward the

Confessor, held land in Fen Drayton and Swavesey ; tenants of his held land in

Boxworth, Conington and Elsworth. All this land became the property of Gilbert

of Gand. Other Saxons mentioned, who may have been

resident landowners, were Balcuin of Madingley, Osulf and Gold of Willingham, Lefsi

of Swavesey and Boxworth, Hugh at Long Stanton and Godwin at Over,

Of the forty-four tenants-in-chief,

who held Cambridgeshire land from the King in 1086, sixteen held land in the

area we are considering. The King, himself, only held land in Fen Drayton. The

Bishop of Lincoln had land in Madingley and Childerley. The Abbey of Ely had

seven hides in Willingham. The Abbey of Ramsey held land in Elsworth, Boxworth,

Fen Drayton and Over, as well as the whole of

Knapwell. Crowland Abbey had seven and a half hides

in Dry Drayton, while the Nunnery of Chatteris held

one hide in Over, worth 16s. The Church, in fact, was a substantial, perhaps

the dominant, landowner in the district.

Perhaps the biggest lay

landowner was Alan de Zouch, Count of Brittany. He

held the main manor in Swavesey with a mill and a fishery rated at 3,750 eels

annually. Monks of Swavesey Priory were the Count’s tenants for lands in Dry

Drayton. Count Alan also held land in Fen Drayton, Boxworth, Willingham, and

Long Stanton. Harduin de Scalers

and Picot, the Norman Sheriff of Cambridgeshire, both held large areas. Harduin had land in Elsworth, Over, Conington, Boxworth and

Dry Drayton, Picot in Pen Drayton, Over, Willingham, Long Stanton and

Childerley, as well as the whole of Lolworth. While Knapwell and Lolworth were

single manor villages, with a single owner, most of the villages had several

owners and several manors

The change brought by the

Conquest was not merely one in the personnel of the tenants-in-chief, the

landowners. There was a general decline in freedom. Before the Conquest there

had been 144 sokemen in the area, free peasant

farmers not subject to a lord; by 1086 only 39 were left. It is no accident

that, of the 105 who vanished, 102 were on the estates which became Harduin’s and Picot’s. These two Norman lords had an

unenviable reputation for the destruction of a free peasantry in other parts of

the country as well as in our area. They carved their manors out of free

peasant lands. A foreigner is recorded as living in Elsworth in 1086.

From Domesday Book we learn

that there were watermills at Swavesey and Lolworth, that

at Lolworth was out of use and paying nothing. As well as Count Alan’s fishery

at Swavesey, Gilbert of Gand had a marsh, rated at

225 eels. There was a marsh in Long Stanton, rated at 3,200 eels, and one at

Over worth 6s. 4d.; at Willingham there was a mere

worth 6s. Wood for houses is recorded at Elsworth and wood for hedges at

Knapwell, Lolworth, Childerley and Madingley.

With the passage of time

the Church holding increased; the de Zouchs granted

Swavesey and Dry Drayton land to the Priory they founded in Swavesey, as a

branch of the Benedictine Abbey of Angers. Boxworth, Conington, Lolworth, Long

Stanton and Madingley belonged to a succession of lay lords through the middle ages ; several families, e.g. de Boxworth of Boxworth,

Elsworth of Conington, actually took their names from the villages. The de Zouchs of Swavesey alone among the lay lords of the manor

were powerful locally and appropriately, had a castle in Swavesey. The rather

puzzling earthworks at Castle Hill, west of the village street, seem to be the

site of their Castle, but little can be learned of its nature from them. At

some time during the middle ages Madingley became the shire manor it was held

in trust for the county and farmed for £10 a year, which sum was used to pay

the wages and expenses of the Knights of the Shire, the County’s M.P.s. In 1543 an Act of Parliament confirmed this manor to

John Hynde and his heirs in return for continuation

of this payment, discharging the inhabitants of Cambridgeshire of all future

responsibility for the fees and wages of their M.P.s.

THE PARISH CHURCHES

The Church was present as a

landlord in many of our villages, but in all of them there existed a parish

church, often the only stone building in the village and the centre of its

life. It is impossible in a short space to do justice to the parish churches of

our area. There were no churches recorded here in Domesday Book. At Over there

is a later record of a Cross near the path leading to Mill Pits and possibly

there was another at Stump Corner near Willingham. Crosses were erected for

open air worship in Saxon times. The first churches were usually wooden and

probably such buildings existed in many of the villages. There was an

Anglo-Saxon burial ground in Over near Bridge Causeway (now Chain Road). The Bishop

of Ely granted a licence to build a new Church in Over in 1264, the previous

church having been burnt down. Long Stanton All Saints may have had a Saxon

wooden church; Elsworth church was mentioned in a grant to Ramsey Abbey of the

tenth century. The only surviving evidence of Saxon stone work is in the

fragments of Norman columns in Willingham church south porch, one of which is

made from a Saxon grave cover, and possibly, in the open slit near the east end

of Fen Drayton church.

Dating the surviving church

buildings is difficult because of extensive nineteenth century restorations.

Comparison of the present structures with the remarkable drawings and

descriptions made by William Cole of Milton in the eighteenth century reveals

that many apparently old features are really nineteenth century work. Boxworth

church has Norman masonry in the south wall, however, but in most of the

churches the earliest genuine work is of the early fourteenth century. Long

Stanton St. Michaels is an exception, being a remarkable church of about 1230. Madingley church in the main dates from about 1300.

Naturally the bigger villages had finer churches. Ely Abbey at Willingham were

responsible for a magnificent church with a double hammerbeam

roof; the angels were added later, during nineteenth and twentieth century

restorations. Swavesey and Over churches are outstanding. An interesting

feature is the common style in certain churches which suggests a common

builder. Thus Dry Drayton and Swavesey churches have similar tracery in the

chancels, significant when we remember that Swavesey priory was a landowner in

Dry Drayton. Lolworth church has a fragment of frieze with ball-flower ornament

and flowers along a tendril. An exactly similar frieze is in Over

church’s south aisle, dated between 1320 and 1330. Over church has a stone

bench around the inside of the outer wall; the purpose for which this was built

reminds us of the proverb, ‘the weakest go to the wall’. There is a fourteenth

century Sanctus bell in the church.

The churches contain many

tombs and monuments too numerous to mention individually, but several are the

work of outstanding sculptors. Conington has work by Grindling

Gibbons in marble, There is much interesting church furniture too, fine early

Tudor Chancel stalls at Elsworth, a thirteenth century chest at Long Stanton

St. Michaels for example.

Parishes were initially

endowed by local landlords, who retained the right to present a successor to

the living when the priest died or removed. This right, the advowson, passed

through many hands. At Boxworth and Lolworth the advowson has always been in

the hands of laymen, the successive lords of the manor. At Dry Drayton,

Elsworth and Knapwell, the advowson was in the middle ages in the hands of an

abbey; Swavesey Priory in the first case, Ramsey in the other two; after the

dissolution of the monasteries it passed into lay hands. The Abbot and later

the Bishop of Ely had the advowson of Willingham from the beginning; he

acquired that of Conington in 1282 by gift from the Elsworth who was lord of

the manor. Swavesey passed from the local Priory to the Bishop at the

Dissolution and later came to Jesus College, and Long Stanton All Saints came

to Ely by Queen Elizabeth’s gift; it had been given by the lord of the manor to

a Collegiate Church in Lincolnshire and passed to the Crown in Edward VI’s reign. The advowson of Madingley also belongs to Ely.

Four Cambridge Colleges today own the advowsons of Swavesey, Fen Drayton, Long Stanton St. Michael and Over. Fen Drayton was granted to

a Breton abbey, and let by them to the Priory of Swavesey; when the advowson

came into the King’s hands he granted it to Christ’s College. Over belonged to

Ramsey Abbey and after the Dissolution was granted by the Crown to Trinity

College. Long Stanton St. Michael had a chequered career. There was a dispute

about the advowson in the thirteenth century between the de Cheyney

and de Colville families, a reflection of the barons’ war (see page 17).

Although the King had control for a time the advowson remained in lay hands

until a purchaser, Edward Lucas of London, gave it to

Trinity Hall.

The Master of Trinity Hall

left it in his will to Magdalene College. Clearly the quality of the local

priest in each village depended in part on how the advowson was used and who

by. When Trinity College obtained Over and the Bishop

of Ely Long Stanton All Saints, they took the rector’s land and tithes for

their own use and installed a less well paid Vicar. At Long Stanton the owner

of Bar Farm was at this time made responsible for the maintenance of the

Chancel roof and for the payment of £20 a year to the Vicar. Fen Drayton was

served by non-resident College Fellows, who only too often failed to arrive for

the Service.

DAILY LIFE IN THE MIDDLE AGES

The church and the lord of

the manor dominated the life of the medieval village. Naturally they left

behind them plentiful documentary records, therefore

much of the space in scholarly County histories is filled with manorial and

church history. Less often printed and less well known are the historical

records of the daily life (and death) of the ordinary peasant. To this we

thought it worth while giving some attention. On Monday June 10, 1308 Roger de Kiltone of Conington, giving evidence confirming the coming

of age of John the son and heir of Simon le Havekere,

stated that on the day of St. Clement (23 Nov.) 1284 he held a feast in honour

of the saint, when, all his neighbours sitting to dinner, his oven and kitchen

were burned. On July 16, 1311 John de Conytone gave

similar evidence of the coming of age of John, son and heir of William Heved of Hardwick; he stated that he remembered the baptism

of John, because on that day he lent his houses to a chaplain named William Stebrox, to hold his (the chaplain’s) feast, because he

celebrated his first mass on that day; the same day the kitchen was burned.

These incidents help to

bring home to us why we do not have left in our villages any medieval peasants’

houses. They were simple small one-room huts made of wood, wattle and daub or

clay bat and thatch. The ‘kitchen’ was a separate building ;

even the oven might be detached. Hence the impressive

‘houses’. Such structures caught fire easily and survived rarely. After

all as late as 1913 Swavesey was swept by a devastating fire, in which twenty-eight

old cottages perished and twenty-two families were rendered homeless.

Significantly the Daily Mirror commented “Only the cottages of brick with slate

roofs escaped”.

Even manorial dwellings

were usually built in perishable materials and less permanent than we tend to

assume. In writing of the Ancient Earth works of Cambridgeshire the Victoria

County History notes ten in our area. Only two of these are in the fen edge

villages — Belsar’s Hill in Willingham and Castle

Hill in Swavesey. There is an important castle mound in Rampton. But there are,

significantly, many more in the uplands: 3 in Boxworth, 3 in Childerley, 1 in

Knapwell and 1 in Lolworth. Many of these puzzled the author of the article,

but the comment, quoted about Boxworth, would seem to be the explanation of

most of them. “This village was accounted the seat of the Barony of the Hobridges, or Boxworths, men of

great honour and reputation in their time, who changed their names as they

altered their dwellings, frequent in those times.” The sites of two of Long

Stanton’s four medieval manors can be identified. Nicholas de Cheyney had a manor house at the Mound at the southern end

of the village. A moat can still be seen in the wood below All Saints’ Church

which probably surrounded the manor house of Ralph de Toni.

Insecurity in one’s home

was probably balanced by the ease of building a new home in local materials.

The general insecurity of life may have been taken for granted but it is none

the less true that the threat of death was ever present, as compared with our

times. Famine was not infrequent ‘the great dearth’ of 1285-8 led to many

deaths from hunger and cold, recorded at Swavesey and Elsworth; significantly

at Childerley thefts which occurred at this time were practically all overlooked.

The famine of 1340 arose from a drought which destroyed the spring corn and

peas in many parishes. The range of local crops is indicated in a table,

printed in the Victoria County History, which summarizes the average acres in

Dry Drayton sown annually in the C13 and C14 to various crops: wheat 40; oats:

30; peas: 13; barley: 8; maslin (mixed wheat and

rye): 6; rye: 3. Between 1348-50 plague, the Black Death, attacked the

inhabitants ; while the records of Elsworth show no evidence of deaths due to plague,

at Dry Drayton 20 of the 42 tenants died, and presumably many more wives,

children and landless men. Willingham alone seems to have increased in

population in the mid-i4th century, in spite of the Black Death.

SUDDEN DEATH

Accidental death was frequent,

although there were no motor cars or faulty electric wiring to kill people. At

Boxworth the Court Roll records how Agnes Prat found

Margery, the wife of Henry Rok, drowned by falling

into a pond in her garden while cutting bushes. At Swavesey John, the ten year

old son of John Walton, was getting water from a pond in John Hold’s Wineyard close; the pond was frozen and he went onto the

ice with his yellow pot ; the ice broke, he fell in

and was drowned. We are told that the pot was worth 1s 6d. This macabre detail

was included in the contemporary record, because the pot, connected with the

cause of death, became a deodand or gift to God; later such items or their cash

equivalent were forfeit to the Crown. Drowning was a frequent cause of death.

At Swavesey Margery and Will Ede were found drowned in a ditch in Edward I’s reign; and in the same reign it is recorded at Swavesey

that Geoffrey, the son of Gilbert, fell from a boat in the Fen and was drowned.

The value of the boat was meticulously recorded at 1s. and

of a horse at 16s. 4d; was the boat being towed?

A domestic tragedy is

recorded at Lolworth in 1353: a boy of two, playing at home, fell backwards

into a pan of fermenting ale and hurt himself so badly that he died in six days

the price of the pan and the ale (October, that is strong ale) was 2d. At

Boxworth in 1348 a girl was accidentally killed by a horse; at Childerley in

1356, John Bond, riding an old horse, worth 3s. 4d.,

in the fields, fell off and broke his neck. In 1359 William the Clerk of Boxworth

drove his cart with a load of dung into Boxworth field; he wished to ride on

the cart on the way back. In getting up his leg caught between the cart and the

horse and he fell backwards ; the horse in the cart dragged him a long way over

the field and for a long time; all the while one of the horses was kicking

William with his hindlegs, and so he died. The cart

and horse with its harness was worth 13s. 4d. The fact

that the medieval parson was also a peasant farmer is vividly brought home by

this tragedy.

Sudden death was not only

due to accident at work and in the home. Violence by human beings was equally

common. At Swavesey in 1285 Peter de Gateway, a servant of Elene

la Zouche, killed John le Parker with a knife thrust

in the belly in 1299. Adam Baker killed William Andrew of Swavesey. Both these

murderers took sanctuary in the parish church and then abjured the realm,

surrendering their possessions, said in each case to be worth 1s. In 1336 about

Christmas time a man tried to take sanctuary in Swavesey church but was headed

off he killed one of his pursuers in self defence. In cases of crime the

community was held responsible, for raising a hue and cry and for the deodand

if the object itself could not be found. This is revealed at Knapwell in 1342.

Emma la Walshaw was led by unknown robbers into

Knapwell field near St. Nedestrete, robbed of her

clothes, and knocked on the head with a club, worth ½d. Her throat was then cut

with a knife, worth 1½d. Since the club which smashed her head and the knife

that cut her throat were missing, it is difficult to know how their value was

calculated! The reason for recording such a fictitious and gruesome detail is

brought out by the legal decision that, since the robbers had fled, the parish

of Knapwell must either produce a club and knife of the appropriate kind or pay

their price, ½d. and 1½d!

Fleeing murderers

frequently sought sanctuary in village churches; we have seen some Swavesey

examples. Fen Drayton Church in 1260 gave sanctuary to Henry, the miller of

Stanton, who, with Robert, the miller of Newsells,

had killed the miller of Shepreth. Robert was caught

and hanged, but Henry taking sanctuary, escaped with his life into exile. No

doubt many of the peasants, to whom the village miller was anathema, as Chaucer’s

tale of the Miller of Trumpington reveals, commented

to the effect “When thieves fall out…. Henry incidentally forfeited 1s. for his goods; the constant repetition of 1s. suggests that the forfeiture may have become a nominal fine

rather than an actual confiscation of all the criminal’s possessions. Fen

Drayton gave sanctuary to two strangers in 1272 and to a male murderer and a

female robber in 1280

UNUSUAL EVENTS

All this may suggest that

violence was the only extraordinary event to occur in the life of a medieval

villager. Two documents about coming of age and relating to Conington, to which

we have already referred, give a rounded picture of unusual local events. It is

improbable that in either case they all occurred on a single day as the witnesses,

asked long after how they remembered a particular day, stated, but it is

probable that the various events described had occurred in the village at about

the time stated. In the first case Richard Golene

(aged 60) recalls the baptism of John le Havekere

because he had a son Robert of the same age baptized on the same day. John Kaym (50) remembers because he was godfather to John and

gave him ½ mark (6s. 8d.) and a gold ring. William Quyntyn

(54), who had married his wife Thephania a year

earlier, buried her on 22nd Nov. and was almost mad with grief. Roger de Kiltone’s evidence we have already described (see page ii).

John Pollard of Fen Drayton (40) remembers that particular November 23rd

because he was robbed and almost wounded to death by the robbers. William Jek (45), also of Fen Drayton, buried his father, James, in

Conington churchyard on the day John Havekere was

baptized. Wymund de la Grove (58) of Elsworth states

that on the day in question he caused to be read before the parishioners of

Conington the charters of a parcel of land which he bought there

; he took seisin on the same day and was

ejected on the morrow. Robert de la Brok of Elsworth,

William Fraunkeleyn of Boxworth, William Morel of Fen

Drayton, John Pount and William de la Grove of Swavesey

(all 50 or older), caused their staves and purses to he consecrated in

Conington church on Nov. 24th 1284 and began a journey to St. Andrews in

Scotland.

The second collection of

evidence was made on 16 July 1311 to prove the coming of age of John Heved of Herdewyk. Geoffrey (46),

John’s godfather, stated that John was twenty-one on 21 March 1311 for he was

born in Conington on that day in 1289 and baptized the next day John would

actually seem to have been 22! William Hampt (50)

remembers the baptism because his next door neighbour William Golene died and was buried at that time. William, the Clerk

of Conington (60+ ), buried his father on 20 March

1289. Richard Gokne (48 +) made his homage on 21st March ; presumably he was taking over his father, William’s

holding of land in the manor. John Kaym (43+) married

his sister, Elice, on this day, to John, brother of

the rector of Conington; Kaym, with another named

Henry, led her to the church and back. William Quyntyn

(now described as 52+ three years earlier in 1308 he was 54!) remembers his

wife’s sad death, but now states that it occurred on May 28, 1290; in 1308 he

had stated that she was buried on 22 Nov. 1284. This is interesting

confirmation that the events, so glibly described as all occurring on one day,

were probably in fact the local sensations of several years. Quyntyn goes on to add a further detail, that he was

excommunicated by the rector in the church for selling an ox on St. Benet’s day

(21 March). Bartholomew de Glemesford (50+) remembers

the baptism because his own son, John, was baptized on the same day in the same

water. Wymund de la Grove (70+), on March 21st,

married one Isabel and William Heved, John’s father,

was at his house at a feast and told him of the birth of John. William More

(80) remembers the day because his son, Henry, on that day set out on a

pilgrimage to Rome and never returned. Robert Stebrox

(60+) remembers the day because it was the day his son William celebrated his

first Mass in Conington and baptized John. William Habraham

(44+) says that on this day his mother Margaret gave him an acre of land in Fen

Drayton and on the next day (22 March) he caused the charter to be read. There

was a celebration of a new Mass at Conington and after it he saw John Heved baptized. John de Conington (41+) then describes how

he lost his kitchen due to lending it to the priest for the feast to celebrate

his first Mass. These two surviving accounts give us, incidentally, a vivid

picture of the kind of events which seemed memorable to local villagers in the

late thirteenth century.

BATTLE

Battle, like murder and

sudden death, disturbed the routine of medieval life. The isle

of Ely was a refuge for rebels and for the defeated for many centuries. Danish

invaders followed the Anglo-Saxon settlers. It is our private suspicion that Belsar’s Hill in Willingham may prove, when excavated, to

be a Danish military camp, rather than the Norman or Bronze Age site it is

often believed to be. Its site in relation to the Ouse and its shape is

reminiscent of Trelleborg in Denmark. The driftway is supposed to have been in use since Norman

times; it was the principal line of approach to Ely. On the 1836 ordnance

survey map it is shown passing round the site on the east side; so the camp

site should be older. Hereward’s resistance to the

Norman conquest centred on Ely; much of the fighting took place to the south

and east of our area, but, if William’s main attack around Alrehede

was at Aldreth as one interpretation has it, clearly

Willingham and probably many neighbouring villages must have seen much Norman

coming and going. During Stephen’s reign (1134-54) civil war again centred on

the Isle of Ely.

The civil war, which raged

between Henry III and the barons led by Simon de Montfort, left its mark in the

neighbourhood. Simon himself seized Henry de Nafford’s

Long Stanton manor after his victory at Lewes. The incumbent of Long Stanton

St. Michael, a nominee of one of Simon’s followers, Phillip de Colville,

followed his betters’ example with an attack on William de Cheyney’s

manor. After the King’s victory at Evesham his supporters retaliated: Alan la Zouch of Swavesey seized Thomas de Elsworth’s

lands in Swavesey and Conington. The disinherited members of the baronial party

fled to Ely in 1266 and made the island once again a centre of resistance. They

raided and plundered for food in the surrounding countryside, concentrating on

the lands of the church and those of royal supporters; Crowland

abbey lands and buildings and the parish church at Willingham were attacked, as

were the conventual buildings of Swavesey priory. No

doubt an attack like this explains the grant of free corn obtained by Alan la Zouch in

1267, because his corn at Swavesey had been burned by the King’s enemies. In the same year Simon of Swavesey needed a safe conduct to go to the King’s Court.

TAXATION AND THE PEASANTS’ REVOLT

Royal taxation on top of

manorial dues can never have been popular. This was usually presented as

taxation for war. In 1316, for example, Cambridgeshire villages had to raise

money for the Scottish war. 19s 4d was raised from the village of Fen Drayton,

an average of 8d. from each taxable person; 6s 8d of

this money was used to buy one aketon with bacinct. For the Lay Subsidy of 1327 £7 13s 9d was raised

from 546 people of Over, £9 3s 2d from 576 people of Swavesey, £5 6s 8d from

258 people of Willingharn, £1 10s from 162 people of

Fen Drayton, and £1 8s 7½d from Knapwell. The highest sums paid in each village

varied from 2s 9d in Knapwell to 12s in Swavesey. The differences clearly

represented differences of wealth among the taxpayers, but the tax may well

have fallen unequally as between villages and individuals. In 1377 the 111

adults of Fen Drayton paid £1 17s towards the Poll tax. There were four local

collectors John Boleyne and John Beton,

the Constables, and William Maddy and William

Abraham, additional sub-collectors.

In 1381 the peasantry over

much of southern and eastern England rose in revolt against the Poll Tax and

various oppressions by their lords. In many places church landlords were particularly

attacked. Dr. Palmer states that there were no attacks on the Ramsey manors in

Elsworth, Over and elsewhere, but throughout the months after the revolt was

put down the Abbey of Ramsey was issuing commands that its peasants should perform

their traditional services, so there must have been some discontent. John Cook

led a band of peasants north to attack Thomas de Elsworth’s

property at Elsworth, and John Scot of Milton came with a band to Lolworth to

the house of John Sigar, threatening his wife Mabel

that they would pull down her houses unless Sigar

granted them freehold possession of lands in Girton

and Madingley. William la Zouch of Swavesey headed

the judicial commission which put down the revolt with a short reign of terror.

William de Cheyne of Long Stanton sat on the

Commission. Swavesey had had its own troubles, though it is not clear whether

revolt in the village was spontaneous or due to John Cook’s arrival. Fen

Drayton rising was also attributed to John Cook, who was outlawed on June 15th

1381 and his land (50 acres) and goods worth £6 7s 6d confiscated.

PROPERTY RIGHTS AND DUES

Everyday life ought

obviously to bulk larger than the sensational if our account is to be true to

life, but we are faced with the difficulty of either repeating what is common

to every book on medieval peasant life or writing a history of each village,

which is not our intention. There is only space for a few hints. Land in these

agricultural communities was much subdivided and sublet, and so one finds a virgate (the typical 30/40 acre peasant holding) in

Knapwell in 1255 in which many people have some right or other. The details are

difficult to sort out. The virgate had descended to

one William de Schelford who was hanged in London on

11 July for murdering his father. The King’s claim, presumably because of the

murder, was valued at 6s. 4d. saving the corn crop from ten acres already taken

from the executors of John de Schelford who had been

killed. The virgate was held of William Burred for a

yearly payment of a pound of cummin and 1s made to

the heirs of Henry le Eveske, lord of the fee. But

one Emma held three acres and a house belonging to the virgate,

for which she paid 3s to the heirs of Nicholas de Vavasour

and to Silurius Lenveise

the remainder to the virgate which was worth 15s was

described as held of the same heirs. The Schelfords

and Emma seem to have been the actual farming tenants.

The Prior at Swavesey owned

property there and in Dry Drayton; from quite a different aspect his property

reveals equally clearly the complex obligations of ownership in the medieval

village. In 1279 he held the Rectory of Swavesey in his own right and two virgates of Lady Eleanor la Zouch,

paying her 8s a year to hold his own manor court and to survey his tenants’

gallon and bushel measures; these had still to be presented twice yearly in

Lady Eleanor’s court. The Prior also had a fishery, a weir and a fishhouse in the Ouse. In 1285 he was in trouble for

overstocking his Dry Drayton farm. He owned one hide in the parish and his

stint of the pasturage was six oxen, two horses, six cows, eighty sheep and

thirteen geese. He had in fact a flock of six hundred sheep and a herd of one

hundred and twenty mixed cattle. There survives from the late fifteenth century

a record of the Prior’s annual expenses and payments.

|

|

£ s. d. |

|

For

the farm of the parsonage of Swavesey and for the rent of Dry Drayton,

payable on Feb. 2 and Sep. 14 |

37 0 0 |

|

Also in yearly distributions in the parish at the feast of St. Andrew

as much bread as is made of a quarter of good wheat and a ‘Mays’ (a measure)

of red herrings in alms to the poor. |

|

|

Item he gives two acres of marshland to the

farmer of Dry Drayton to the repair of the walls. |

|

|

Item he payeth yearly to the Bishop of Ely |

13 4 |

|

Item he payeth to the Archdeacon |

6 8 |

|

Item to

the prior of Ely |

10 0 |

|

Item to

lord of Swavesey |

8 0 |

|

Item to

the Collector of Brytonmesses (that is the Steward

of Zouch of Brittany’s manor) for Dry Drayton |

2 0 |

|

Item to

the proctor of his fee for answering at the Visitations and Sene (synod) |

3 4 |

|

Item for

the decay of a tenement at the Cross |

3 4 |

This was the

Benedictine priory founded by Alan de Zouch in

William I’s reign, which in 1393 was transferred to

the Charterhouse at Coventry. The mixture of ecclesiastical obligations to

superiors and inferiors with rental obligations to land-lords and the equivalent of local taxes is typical of the obligations which went with property

ownership in the middle ages. A layman would have had fewer ecclesiastical

payments to make and a peasant altogether less to pay, but the same mixture

would have been present.

The obligations of peasant

tenants to their landlords varied. The Victoria County History suggests that

“the conditions of villein tenure were considerably lighter on manors in lay

hands than they were on those held by the Church.” On Ely manors— and Ely had a

manor in Willingham and land in Over—the villein (serf) tenants had to work on

the church’s demesne (home farm) land for “three days a week, before Whitsun

from morning till nones, and after Whitsun until

vespers, ‘and note that no allowance shall be made for any festival in the year

except the day of Christmas’”. While “On the Zouche

manor of Swavesey in 1275 the custom was for 31 villeins to work one year and

the other 32 next year, paying 8d. rent when working

and 2s. 10d. when not.”

“When all the services of the villeins were not required on one

manor they were sometimes sent to another ; thus at

Dry Drayton in 1822, 104 ‘works’ were received from Oakington and 169 from

Cottenham, and in 1327 the Abbot of Ramsey’s tenants at Knapwell did 38 of

their works on his manor of Elsworth.” Dry Drayton, Oakington and Cottenham

were manors of the abbey of Crowland, and they shared

one manorial court. In 1310 Giles de Hyngeston of

Over, according to Mrs. Bold’s history of the

village, took works and rent from some of his tenants but only rent from

others. While Henri Koe owed l0d and 2 capons a year,

John Reynold paid “3s. 2d. and 2

capons, and one man to work for two days (a week) and one man two days in

August and one man to flail at Michaelmas one day”.

In addition “all the homages (owed) wast pennies and the service of

each householder one man one day to make my hay”.

The Church, as landlord,

was stricter than the layman; the peasant, who was personally free, was

normally less burdened than the serf. But sometimes, and especially when the

Church was his landlord, even the freeman had onerous obligations. Ely’s free

tenants had to send their men to work on the boonday.

At Willingham “Thomas Something (Aliquid

or Aucunchose!) who

held a quarter knight’s fee, ‘shall himself ride with them to see that they

work well’ “. “More remarkable is the fact that on many of the Ely manors

(Willingham) free tenants paid heriot, leyrwite, and a fine (gersuman)

for marrying their daughters, such renders being usually considered typical of

villein status.” The Church was not always stricter than the lay landlord. For

at Dry Drayton, as on the other Crowland manors, “some

provision for the aged and infirm was made, until the middle of the 14th

century”, while elsewhere “when a villein became incapable he had to give up

his holding. Widows, however, retained their husband’s holdings as ‘free

bench’, and on the Ely manors (Willingham) it was the custom that when a

villein died from whom a heriot of the best beast was

due, his widow should have the use of the beast for 30 days ‘to the support of

her waynage and should be excused her work-dues for

that time.”

AGRICULTURE

The village arable lands

were unhedged and divided in allotment like strips,

each tenant’s strips being scattered. The rotation of crops was a communal

matter. A similar system was operated in the early days of the Land Settlement

at Fen Drayton; a crop for example, potatoes, would be sown in one field,

irrespective of the holding boundaries and each tenant was expected to do

certain work on the crop at specified times. At Willingham and Madingley the

village fields were divided into three blocks, following a rotation of spring

crops, autumn crops, fallow. At Boxworth and Elsworth apparently a two-field

division existed. The crops grown in Dry Drayton’s fields have been described

on page 12. In the fen edge villages there were many additional special crops

sedge was cut at four yearly intervals for thatching, kindling and litter. Teazles were grown at Over for

dressing wool cloth. Woad was grown in Over and

Swavesey from the 10th century mostly on the south and southwest side of Over

town. It was marketed in Swavesey and taken across the river to Slepe (St. Ives) Market. From St. Ives this beautiful blue

dye was exported to the Continent.

Animal husbandry played an

important part in the village economy, not least because of the value of the

manure. “At Long Stanton if a villein had sheep of his own or of his family he

had to take them to the manor-house, with his own hurdles, from Michaelmas to Christmas”. This was so that the lord could

get the benefit of the manure on his land. Owing to the variations of soil in

the area, the animal stock varied from parish to parish. ‘Thus on the three Crowland manors, between 1258 and 1315, - only Dry Drayton,

on the chalk, had sheep, numbering between 120 and 350 - for the demesne”. In

addition “the tenant of every hide (140 acres at Dry Drayton) had the right to

graze on the commons 6 oxen, 2 horses, 6 cows, 80 sheep and 15 geese.” We have

seen how in 1285 the Prior of Swavesey, who was a tenant of one hide in Dry

Drayton, had 120 cattle and 600 sheep on the commons, Others

followed his example, so Dry Drayton must have had a large sheep population.

The Ely demesne in Willingham in 1277 supported 16 cows (20 in a dry season), 2

bulls, 20 pigs, 1 boar, and 240 sheep. The fenland edge villages had a further

local asset, their fisheries; in 1277 there was on Willingham mere an open-water fishery for three boats, paying the Ely

landlord 30s each. The farming possibilities of the fen edge villages were well

summed up in a survey of Over Manor, made in 1575 ‘a reasonable good soile for corn and grass, yet very barron

of wood and timber. And the pasture and meadow grounds being mares and fenns be for the most parte in the

winter time surrounded with water. And wett partely by soak of the fens lying so near the great River

and partly by rain and water.” Of Housefen the Survey

stated that it “hath ever been time out of minde the

fen wherein the inhabitants of Over have been accustomed to get fodder for the

keeping of their cattle in wintertime - after the first crop or so much thereof

taken as the seasen of the year for wetness and

drought will suffer which is many times uncertain the said inhabitants have

accustomed to spare it till the feast of St. Peter (commonly called Lamas Day)

(1 Aug.) or St. Michael th’ archangel at the discretion

of the Fen greeves and from thence is fed off with

cattle of the inhabitants sans nombre, hoggs, geese and sheep only excepted till it be spared for

hay next year”.

Barefen, Langdridge and Skeggs “have time out of memory of man been Easter Common

to the tenants of Over and Willingham for all manner of cattle sans nombre - in good dry years there was more grass than was

needed”. The assets of living near the fens was balanced by an extra duty, “the

compulsion on a large proportion of the bishop’s tenants to work on the

causeway of Aldreth (which runs through Willingham

parish), which formed the land approach to Ely, or to pay pontage

in lieu of such work”. The affairs of each manor were managed by a local reeve,

“the executive officer, who supervised the actual working of the farm and kept

the accounts”. The reeve might hold office for long periods “at Dry Drayton the

same reeve seems to have served for 30 years”. The 1279 Hundred Rolls informs

us that the Abbot of Ramsey had a Gallows in Elsworth, Knapwell and Graveley and held a court there.

MARKETS AND FAIRS

The medieval village had to

exchange its goods and, therefore, an annual fair and

weekly markets were prized rights. On July 26 1244 Alan la Zouche

and his heirs were granted the right to hold a weekly market in Swavesey on

Tuesdays, and a yearly fair on the vigil, feast and morrow of the Holy Trinity.

In 1261 the Swavesey fair was altered to St. Michael’s day and the five days

following (29 Sep. to 4 Oct. inclusive); in 1505 the fair was moved to Trinity

Sunday again. Swavesey acquired in the early middle ages something of the

status of a market town. From the Hundred Rolls of 1279 we learn that there

were several burgesses in the village, paying rents of between 2s 6d and 5s a

year. They included Henry the Smith, John the Barber and John Medic (the

doctor), as well as several people with surnames. Over Market was in the

rectangle by the Rectory and near the Guildhall; there has been no market held

within living memory. It is possible that Elsworth and Knapwell marketed their

produce at Caxton which lies on the old north road.

POPULATION CHANGES

The graph on page 24 shows

what happened to the population in each village in our area from Domesday Book

to this century. The changes in population provide a summary reminder of the

medieval history which we have been looking at and a foretaste of the following

centuries. Between 1086 (Domesday Book) and 1327, the date of the Subsidy Roll

from which our next figure is taken, all the villages increased in population.

Over, and to a less extent Swavesey, increased in size far faster than the

other villages, to become outstandingly the largest communities. Over increased

its population by three and a half times. The next

figure is from the Poll Tax of 1377; between 1327 and this date, bubonic plague

entered England the Black Death of 1348/9 was followed by lesser outbreaks. It

is not surprising that every village bar one had fallen in population between

1327 and 1377. Willingham was the great exception its population had increased

by nearly 50% when many of the villages had shrunk by between one third and one

fifth. The next return is that made to the Bishop in 1563. There is no return

available for Knapwell and Long Stanton. But the rest of the villages had

differing experiences in the two hundred years from 1377 to 1563. Over,

Willingham and Fen Drayton increased their population considerably; Willingham

became the second largest village in the area, not much smaller than Over. The upland villages did not share in this rise of

population Conington, Dry Drayton and Elsworth remained static in population,

while Lolworth and Boxworth seem to have fallen. The surprising figure in the

return is that for Swavesey, which suggests a population drop of nearly 30%.

Since the next return available one hundred years later shows that Swavesey’s population had increased over the 1563 figure at

a faster rate than any other village, it is possible that in fact the return of

1563 for Swavesey is wrong. Perhaps the parson, making it, underestimated the

size of his congregations.

The Hearth Tax return of

1664 shows a general tendency for population to increase; Willingham has almost

overtaken Over and Swavesey is not far behind; Dry

Drayton, Elsworth and Fen Drayton all had a big increase; but Conington and

Long Stanton dropped in population. When the first government Census was taken

in 1801, Swavesey was the most populated village in the area, and Willingham

close behind with nearly 800 inhabitants; Over had

only 700. Elsworth was the next largest with 580 people, much the most populous

upland parish while Lolworth and Knapwell had the smallest populations, about

100 people each. The next fifty or sixty years saw a rapid population rise in

every village, which was followed by an equally sharp fall until well into the

twentieth century. These changes in population bring out very clearly the

different history, in general of the upland and the fenland parishes. In 1911

Boxworth, Conington, Dry Drayton, Knapwell and Lolworth were not much more

populated than they had been at the time of Domesday Book ; Elsworth alone had

grown considerably ; its population was between two and three times that of

Domesday Book. Of the fenland edge villages Long Stanton had grown least, by a

quarter; but Fen Drayton and Swavesey were about three times as big, Over

nearly six times and Willingham about twenty times as populous as in Domesday

Book.

PART TWO

LONGSTANTON: THE FIELDS FARMING, SOCIAL LIFE AND THE CHURCHES BETWEEN THE SIXTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES

We are able to give a more

detailed picture of the life of the farming community in the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries in one village in our area, Long Stanton, thanks to Miss

H. Margaret Clark, whose research essay is summarized and quoted from in what

follows. Long Stanton consisted of two parishes and four manors, two large and

two small, but it still formed one agricultural unit. Twelve field names are

mentioned in documents from the years 1581 to 1613. These were all unhedged Open Fields, divided in a kaleidoscope of ‘strips’

farmed by different people. In reality there were four of these open fields in

existence in the sixteenth century. They were Mare Field, the largest single

field ; Dale Field, the far end of which was called Allhallow,

Hollow or Farr Field ; Michelow with Littlemore at its north-east end ; and Stanwell

Field, also called Great Mare Field or Haverill

Field; Possel Field adjoined Stanwell

and in the rotation of cultivation they were one unit. The twelth

named field was the Innholmes or Innams;

this included both open field strips and closes. The name suggests that this

ground was added to the existing arable by cultivation of the waste early in

the middle ages. For some reason it was not incorporated in the existing open

fields. The sixteenth century four field system, Miss Clark suggests, may have

developed out of an older two or three field system because of the division of

the village into two parishes ; “the names Allhallows (Long Stanton All Saints)

and Michelow (Long Stanton St. Michael), lying on

each side of the parish boundary of the two parishes, are suggestive”. Clearly

in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the field system of Long Stanton was

undergoing changes. By the end of the eighteenth century ‘there are two

parishes, and in each of them there are three fields, a fallow field, an autumn

field and a spring field. Thus Michelow Field and Littlemore Field and Haverill

Field— lie in St. Michaels, and Mare Field and Hill Field and Dale Field in All

Saints.”

The village fields were

probably some 80% or more arable and there were 150 acres of waste and fen, Cow

Fen in the north-west corner of All Saints Parish. Meadow land usually lay

along the streams, and certain strips in the open fields, usually those too wet

for arable, were cultivated leys. Miss Clark has been able to show from air

photographs and documents that the balks, or ingress roads, which run mainly

south-west and northeast, perhaps “as drove roads leading down to the fen for

summer commoning”, reveal the sixteenth century

pattern of the roads of the village. Just as the open field pattern as a whole

was changing so was that of the ‘strips’ held by each peasant. Consolidation

was taking place and adjoining lands, once held separately, were being put together

to make larger ‘strips’ in single ownership. Out of 152 strips identified, 31

were of an acre or more and nearly two-thirds of half an acre or more. ‘Blocks

of strips in one ownership or tenure came to be called ‘pieces’ at Long Stanton,

and at least ten of these existed by the middle of the seventeenth century.

They were thought of as units in themselves, even if they were only temporary

enclosures. One of these was Castle Piece in the occupation of Henry Edwards in

1626 which remained a distinct unit and was described in the eighteenth century

as “containing 30 lands”. This consolidation of plough lands into larger strips

and of groups of strips into pieces logically led to enclosure and the break up

of the open field system with its rights of inter-commoning.

“The transition from open field ‘lands’ to ‘pieces’ to closes, which may have

become permanent, may be seen on the land of Sir Fulkc

Greville”. Further small scale enclosure to create

improved pasture was taking place. While arable in the open fields was valued

at 4s an acre and the leys at just over 4s the acre, enclosed pasture was

valued at sums varying from l5s to 25s an acre. The motive behind this kind of

enclosure is obvious, but it did not go very far; the village remained basically

an open field one, like most Cambridgeshire villages, until the Enclosure Award

early in the nineteenth century. Indeed, Sir Fulke Greville’s enclosure of the common of the manor held by him

aroused local protest “Sir Fulke hath all and kepes incloses where there should

be comon for ye queenes

Rectory and ye towne ‘; “it will be . . . to the

utter undoing of most or all of us, and our prosperities for ever, with an endlesse curse to light upon th’offenders”.

The protest was in vain.

LONGSTANTON FARMING

How were the village lands

farmed? There were “large tenant farmers of over 100 acres, like the Phypers and Edwardes, and

freeholders like the Bostons”. There were “cottagers

with their acre of close and acre of arable”. “Barley was the main crop. Wheat

and rye were little grown in comparison with barley and, when they were grown,

were grown together.” An account of 1626 for the demesne of Colville’s Manor

gives the yields of different crops as barley 20 bushels, wheat and maslin 15 bushels, ‘grey pease’

16 bushels, and ‘white pease’ l3½ bushels, all per

acre. In 1794 Vancouver gave Long Stanton figures as barley 24 bushels, rye 24

bushels, wheat 18 bushels, peas and beans 16 bushels per acre. Although the

arable was the most important part of the farms, stock was already significant.

But the number of beasts kept varied a great deal. Nicholas Bonner left 56

sheep in his will of 1549 but William Edwardes only a

ewe and lamb in 1591. William Fromant had 19 cows in

1547 but John Christmas only a single heifer in 1565. “The basic stock bequeathed

to the children of a prosperous husbandman is like that which William Fromant left to each of his three daughters in 1547 “10 ewea, 2 mylch kyen,

2 steeryes, a baye horse

colt and a pyed meare

colt”.

“So the economy at Long

Stanton was based on the growing of barley, peas and beans, and a little wheat,

and on the raising of sheep, cows and pigs, products which were eked out by

hens, ducks and geese in the yard, and the bees of the beekeepers.”

SOCIAL CHANGE IN SIXTEENTH & SEVENTEENTH CENTURY LONGSTANTON

Miss Clark has studied the

rise in Long Stanton’s population in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries,

and the social changes that accompanied it. 39 people were taxed in 1542; there

were 42 families in 1563 and 56 houses in 1662. The 38 taxpayers of 1524 can be

divided into three groups thirty paid £4 or less, seven between £4 and £10 and

two paid far more, Christopher Burgoyne £26 and another £29. By the end of the

sixteenth century “at least seven tenants held farms of about 100 acres, besides Buckleys farm, called ‘the Greete

farm’, on Cheney’s manor alone”. Intensity of family feeling helped to

consolidate farms and assisted the family’s rise in the world. Robert Boston in

his will of 1593 “provided that no part of the premises be

alienated ‘soe longe as

there be anie alive of my name or bloude’”.

John Edwardes, who died in 1570, was a husbandman,

but his son Henry, who died in 1626, was a yeoman, as were two grandsons. Other

families declined in wealth and status. “The division between rich and poor,

social group and social group, was not a rigid one. The marriages show that.

Two Edwardes daughters married Wingfields,

who were small husbandmen, in the seventeenth century. Nor

were the terms ‘yeoman’, ‘husbandman’, and ‘labourer’ rigidly used. It

was comparatively easy to slip from one group to the next”. Incidentally

‘labourer’ in Long Stanton was not used for one supporting himself by wages,

necessarily. William Wingfield of the Green Row had a

free cottage, and also held lease from Hatton of £4 per annum, which his widow

maintained’’.

The background to this

social change is interesting. Leases were long, 21 years, and rents at least

between 1590 and 1629 were static. About this time copyhold property became

leasehold. Miss Clark has noted another change: doweries

left in wills tended to be in kind early in the sixteenth century and to become

cash payments by the end of the century. Even “labourers like William Persefalle in 1642 left his daughter 40s, while William Wingfield of the Green Row left his three daughters £3 or

£4 each”. At the other end of the scale “John Phipers, ‘yeoman’, in 1608 left two of his daughters £40

each on marriage”. “In so far as it is possible to generalize, a

‘husbandman’s’ provision for his daughter tended to be £5 or over, in the first

decades of the seventeenth century, and ‘labourers’ with leases on the side,

like Wingfield of the Green Row, left somewhat less.

Cottages with an acre or so might leave a few shillings”.

HOUSES AND FURNITURE

Careful study of the wills

has given Miss Clark a picture of the houses of the village and their contents.

It seems that the rebuilding of houses, partitioning off into separate rooms

and equipping with improved furniture began earlier in Long Stanton than in the

west midlands. As early as 1516 there is a reference to “under the steyrys”; even if only a ladder is meant, this suggests an

early beginning of the process of boarding over a house previously open to the

ceiling, to create upper rooms. There are other references to several rooms in

the house. “The extension of houses was proceeding fast among the smaller husbandmen, it was not out of the ordinary for them to have

one room upstairs, or a chamber, in the second half of the sixteenth century.

Two or more rooms upstairs were probably common among the most prosperous

villagers. At the other end of the scale, the better off labourers were

subdividing their houses into two rooms”. The will of John Hatch, labourer,

made in 1662, refers to “the new house next John Bonds’ and describes how this

single-roomed house should be divided if his son marries “he shall of his owne cost …. build and sctt up a sufficient Chimney in the said new house for the

use of my wife”, i.e. divide the house into two rooms. The Hearth Tax Returns

of 1662 show that only 21 out of 57 houses had single hearths,

i.e. were houses of two or three rooms; the remainder were still larger.

Furnishings, as well as

houses, were getting better. In 1555 the Priest of All Saints had ‘a grete turnede chaire’;

in this he was not alone, but he was unique in possessing books. By the end of

the sixteenth century “the most prosperous possessed joined beds and often had

feather beds to go with them. Trundle beds came in in

the seventeenth century to go with them. No-one could rival Widow Hall in

magnificence, however, for in 1613 she bequeathed a bed which she had bought

from George Rilands, Gentleman, who had settled in

the village. She left it “with the furniture, that is

the bedsted a Canopie and Curtaynes a feather bedd a flock-bedd twoe boulsters

sixe pillowes a Coverlett and a paire of blanketts with a trundlebedd belonginge to the same”.

Elene Brook, the widow of a substantial husbandman,

died in 1553 leaving a chair, two ‘Quysshens’ and a

great leather ‘Quysshen’ among other things. By 1576

‘painted cloths’ and hangings appear in Joan Butcher’s house. “Elizabeth Fromant has a hanging by her bed in 1592, and Agnes Fromant had a bed with painted hangings round it, as well

as three other hangings in 1599”. “The odd half-dozen plain napkins were becoming

common in the houses of husbandmen and yeomen”. The different situation of rich

and poor, but the rise in the standard of living of both, is brought out in two

wills of 1628 and 1635. Joan Blose, widow of John,

who held the smallest lease, £1 a year, from Cheney’s Manor, left “a cupboard,

two hutches, one bed and appurtenances, three pairs of sheets, two towels, two pillowbearers, eight yards of ‘wolinge

clothe’, four yards of linen cloth, three aprons, two pewter platters, one

chair, one stool, one plank, one form, one brass pan, one gown, one wollinge wheel’ and a new sheet.” The furniture is meagre

enough but it includes articles like the chair and the towels which would

certainly not have been there a hundred years before.

The change at the upper end

of the scale is shown in the goods of Katherine Stewkin,

wife of the largest freeholder, who died in 1635, leaving “one cup and six silver spoons … my long tabell and my little Joyne tabell with a ioyned formc and a settle a press Cupboard and my Joine Bedstead one feather bed and two bolsters and straw

bed with mattress and corde one paryre

curtaynes and curtayne

rods and the best Chestc and redd

chest and my copper panne and a broad pann one Spitt and a paryre of pott rakes and my

trundle bed with a redd blanket and a white one the

best Coverlett and a mattris

and ioyne chaire and

straw-bottom charyre and my wollen

wheel and my linnen wheele”.

OVER FENS

The two developments which

were to affect our area most in the sixteenth, seventeenth and later centuries

were of national as well as local importance. They were the draining of the

fens and the Reformation which separated English Christians from the Roman

church.

The Romans had made use of

the fen area for arable cultivation. Neglect and destruction of Roman works by

the English invaders and changes in the relative level of the land and the sea

had turned the fen into a great mere and marsh from which countless fish and

wild fowl were to be won to the benefit of the local inhabitants. At the same

time land on the edge of the fcn was regularly

flooded and so provided good grazing for large numbers of cattle. We have seen

the references made in the 1575 Survey of Over to “the fen wherein the

inhabitants of Over have been accustomed to get fodder for the keeping of their

cattle in winter time” and to “cattle - sans nombre”.

“In good dry years there was more grass than was needed” but the “cattle within

wet years, when the fens be surrounded with water,

were in danger to be starved for lack of Fodder.” To meet this eventuality the

Abbot of Ramsey, in the reign of Henry VII, had divided up the manorial demesne

into ‘Penny Lands’, let out on copyhold tenure, ‘to such as at that time would

give most rent and farme’, to provide ‘strawe and stovcr for their

cattle within wet years’. This was possible because, as the Survey makes clear,

“there was no Mansion House or Manor House or place’. The jury making the

Survey were most concerned about this: “at this present there is not any Capitall Mansion or Manner place or any mention thereof,

other than one close of pasture containing by estimacon

six acres called the Berry yard which some so report to be the place where the

chief house was builded yet is there at this present