|

|

|

| BACK |

THE

SACRISTY

The

Church of

ST.

MARY & ALL SAINTS

WILLINGHAM,

CAMBRIDGESHIRE

The

Case for an Anchorhold

Jeremy

Lander, Freeland Rees Roberts Architects

March

2005

In collaboration with Randolph and

Laura Miles |

CLICK HERE

FOR PDF FORMAT

(970 kBytes) |

|

|

|

| 1. Introduction

|

Some pictures can be enlarged by

clicking |

|

This paper is the result

of preliminary research following a conservation and repair project

carried out by Fairhavens of Anglesey Abbey under the direction of

architects Freeland Rees Roberts in the Autumn of 2004.

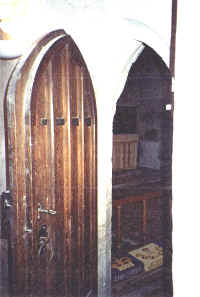

The ‘Sacristy’ at Saint Mary and All Saints Willingham, situated

on the north side of the chancel, had fallen into disrepair. Its unusual

construction, an interlocking ashlar stone roof without a weathering

surface (i.e. no tiles or lead), had led to rain ingress through the

joints and considerable algal and mould growth had built up on the

internal roof surface. An initial report by conservators Nimbus

Conservancy recommended the raking out and re-pointing of the stonework

joints with hydraulic lime mortar. Combined with localized replacement of

severely damaged roof stones and other conservation measures this work has

now been completed.

Although

referred to as a Sacristy the original use of this small but beautiful

chapel-like structure has never been determined and it was by chance that

one of the staff at Freeland Rees Roberts, Randolph Miles, visited the

site and surmised that the use could be that of an ‘Anchorhold’. His

wife Laura Miles is studying Mediaeval English at Selwyn College Cambridge

and the subject of her MPhil project is the literature of Anchoresses. But

what is an Anchorhold? |

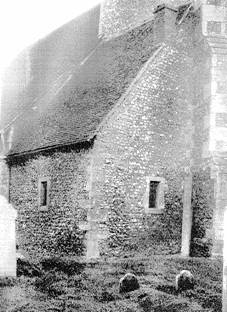

Sacristy prior to conservation work

After work completed |

| 2. Anchorites

and Anchorholds

|

|

|

From as early as the 7th century AD until the

reformation a substantial number of religious people lived hermitic lives

in England and all over Europe. It appears that they were most common in

the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries. Many lived in caves and rustic huts in

remote places but there were others who were attached - quite literally -

to churches. These people were called anchorites (fem. anchoresses) from

the Greek anachoretes meaning "one who lives apart". A cell,

called an 'anchorhold', would be built, sometimes in the churchyard or

other part of the village, but often adjoining the church itself [note].

There were no rules as to the situation of the dwelling but it was often

on the north side of the church so the anchorite could "deliberately

forego the sunshine with the rest of natures gifts" [note].

Once the cell was ready the anchorite would be 'enclosed' there,

devoting themselves to prayer and devotion, sometimes for the rest of

their lives. The bishop had to vet all candidates carefully for the

decision to be enclosed was an extremely serious one and it was an

embarrassment if the anchorite left the cell early for some reason, as

happened at Shere in Surrey in the 14th century when an anchoress left her

cell after three years and was ordered by the bishop to return 'on pain of

death' [note].

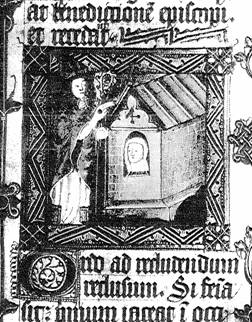

Because they were removed from normal life the enclosure ceremony was

similar to a funeral service, the anchorite being considered "dead to

the world". The order of enclosing provided that the candidate should

fast and make confession, keeping vigil throughout the preceding night.

After the mass and prostration before the altar he or she would process

with the bishop and clergy, carrying a lighted taper, to the cell, the

bishop leading whilst clerks chanted a litany. After solemn prayers the

door would be shut and the procession would return to the church [note].

In many cases the anchorite was literally 'walled up', though they were

usually locked in with the door locked or barred from the outside.

Occasionally the anchorite would even venture from the cell, to dispense

teaching and alms to the community, the amount of time they spent in the

outside world being left as a matter of conscience rather than

imprisonment. They might also receive visitors; children, for example,

could be given lessons, or a priest enter to say mass or hear confession.

Sometimes they had servants and in some instances there would be more than

one anchorite with two or three lodged together in adjoining cells.

More commonly there would be one solitary anchorite and he or she would

remain confined in the anchorhold, out of sight from the common populace.

The cell communicated with the church, usually the chancel, so that the

anchorite could watch and take part in church services. Through an opening

they could pray to the Blessed Sacrament; on the opposite side there would

be a small 'parlour' or 'world-side' window through which they could

receive food and communicate with the outside world though remaining

hidden by a shutter or curtain, often a black cloth bearing a symbolic

white cross [note].

If the inmate were a priest the cell would be made a consecrated

oratory but even if not the anchorhold could still be provided with an

altar as recommended by Aeldred (an 11th century bishop and manual-writer

for anchoresses): "arrange thine altar with white linen cloth"

he wrote "which betokeneth both chastity and simpleness..In this

austere setting set an image of Christ's passion that thou may have mind

and see how he set and spread his arms to receive thee and all mankind to

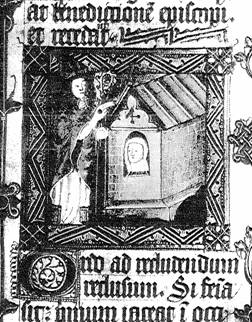

mercy if thou will ask it". |

Enclosing an Anchoress

Saint Fremund's Hermitage |

| 3. The Lives of Anchorites

|

|

|

In her

book, The Hermits and Anchorites of England (pub. 1914) Rotha Mary Clay

describes a typical candidate for enclosure: “The would-be anchoress

might be some maiden ‘without the habit of a nun’ who desired to

devote herself to religion in the village where she had been brought

up…she might be one who affects the solitary life”. They were

“usually attached to a church in order that

they might derive spiritual advantages from it

and at the same time confer spiritual benefits on the parish.” [note]

Anchorites were not expected to support themselves, and, although

there is evidence of them living by the ‘labour of their hands’,

trading was frowned upon. Usually, prior to enclosure, the anchorite would

have to make arrangements for people, from the local manor for example, to

provide them with sustenance. The bishop was careful not to license anyone

unless he was satisfied that such arrangements were secure and permanent [note].

Alms could be received and by the 15th century this had become

a lucrative source of income for some anchorites, attracting the

disapproval of many commentators of the day.

Usually however anchorites lived in extreme poverty, sustained by

simple, chiefly vegetarian, foods.The ‘Ancren Riwle’ (a rule book for

anchoresses written by a 13th century bishop) warned

anchoresses not to grumble if these were inedible. They might ask for more

palatable food but reluctantly and tactfully ‘less men say this

anchoress is dainty and she asks much’ [note].

There was no regulation dress but in winter a pilch or thick garment to

keep out the cold and in summer a kirtle with mantle, black head-dress,

wimple, cape or veil. The one stipulation was that the dress must be

plain.

It is hard for us, with our modern, sanitary lives to imagine how

normal bodily functions could have been accommodated. There is little

detail about this in the accounts of the time, probably because the

standards for the general populace were so basic, but it is likely that a

simple latrine would be dug into the floor. The anchorite was encouraged

to wash, however and although extreme ascetics gloried in squalor the

various rules for anchorites did not encourage personal neglect. One

directs “wash yourself as often as you please” another quotes St

Bernard “I have loved poverty, but I never loved filth” [note].

The keeping of animals was also considered carefully by the manuals. The

Ancren Riwle states charmingly: “you shall not possess any beast, my

sisters, except only a cat…Christ knoweth it is an odious thing when

people in the town complain of anchoresses’ cattle”.

The Anchorite was warned to watch their health, flagellation and the

wearing of hair shirts was expected but wanton self-neglect was seen as

counter productive, getting the balance right was clearly not easy. The

Ancren Riwle says “let not anyone handle herself too gently lest she

deceive herself. She will not be able to keep herself pure ..without two

things: the one is giving pain to the flesh by fasting, by watching, by

flagellations, by wearing coarse garments, by a hard bed, with sickness

and much labour; the other thing is the moral qualities of the heart,

devotion, compassion, mercy, pity, charity, humility...yet many

anchoresses are of such fleshly wisdom and afraid lest their head ache and

their body be too much enfeebled, and are so careful of their health, that

the spirit is weakened and sickeneth in sin”.

The Riwle also warned anchoresses not to think that enclosure would

get easier as the years passed. It warns of the later years, with

temptations unabated, when she might think that after such a long period

God had quite forgotten her: “An anchoress thinks she shall be most

strongly tempted in the first twelve months…nay! it is not so. In the

first years it is nothing but ball play”.

One fault was considered to be that of sitting too long at the

parlour window. “Love your windows as little as possible”, cautions

the Riwle, “and see that they be small”. It warns of bad women who

will come to the window whispering soft words and putting wicked thoughts

into the anchoress’s head so she cannot sleep [note].

Putting out a hand through the window, to heal the sick for example, was

frowned upon.

On the subject of servants Aeldred advised: “First choose an

honest ancient woman…no jangler, no roller about, no chider, no

tale-teller but such one that may have good conversation and honesty. Her

charge shall be to keep thine household...to close thy doors and to

receive that should be received and to avoid that should be avoided. Under

her governance should she have a younger woman to bear greater charges in

fetching of wood and water and setting of meat and drink”. The Ancren

Riwle stipulated that the older woman who went about the village should be

plain and the younger one kept inside as much as possible. It was

inevitable that gossip would be brought back to the anchorhold by these

servants and recycled to passers-by at the parlour window. A common saying

was ‘from mill and from market, from smithy and from anchor house men

bring tidings’.

At the end of his or her life the anchorite was often buried in the

anchorhold. Six skeletons were found at

Compton

in

Surrey

beneath where the anchorhold would have been [note].

Sometimes the grave would be made ready at enclosure and kept open as a

memento mori, the anchorite bidden not just to meditate on their own

mortality by staring into the empty grave but, with their bare hands, to

scrape up some earth from the pit each day [note]. |

Anchorhold at Hartlip

Warkworth Hermitage

Anchorite's squint and doorway at St Julian's, Shoreham |

| 4. Julian of Norwich |

|

|

The most famous English anchoress was Julian of

Norwich (1342-1412). She prayed for illness as a penance and got her

desire at the age of 30. She nearly died in her mother's arms but survived

and lived for at least another 40 years. Her writings, known as the

'Revelations of Divine Love', describe in detail the "shewings"

she experienced during her grave illness, and are thought to be among the

finest contributions to religious literature produced in England. She is

best known for her optimism with such words as "All shall be well,

and all manner of things shall be well", and for a kind of early

feminism insisting, as she did, in calling God and Christ

"Mother." |

|

| 5. The Demise of Anchoritic Life |

|

|

With the coming of the Reformation the practice

of paying religious people, through alms or otherwise, to pray for and on

behalf of their benefactors became discredited. Prayer and devotion to God

began to be seen as the responsibility of every individual and not

something that could be assigned to others, however religious or selfless

they may be. Hermits and anchorites became anachronisms and numbers began

to decline. When the monasteries were dissolved in the 16th century

anchorites disappeared from the scene altogether and the anchorholds were

either pulled down or put to other uses, such as vestries. |

|

| 6. Willingham Church |

|

|

St Mary

and All Saints is a large parish church in the centre of Willingham, a

village on the edge of the fens 12 miles to the

north west

of

Cambridge

. From Bronze Age times until the mid 18th century Willingham

lay on the main route from

Cambridge

to Ely via the Aldreth Causeway, and later by means of the bridge at

Earith. Being on this important route large processions of ordinands,

sometimes as many as 300, processed through Willingham to Ely on a regular

basis.

The church was officially founded in 1244 but there is evidence of a

Saxon church and a Romanesque building on the site [note].

Most of the current building dates from the first part of the 14th

century with the tower added in about 1340 and the spire shortly after [note].

The church is famous for its wall paintings that decorate most of the nave

walls. |

|

| 7. The Sacristy |

|

|

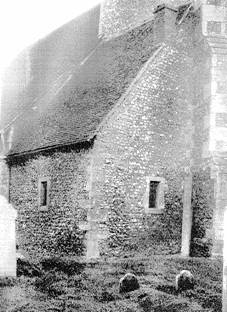

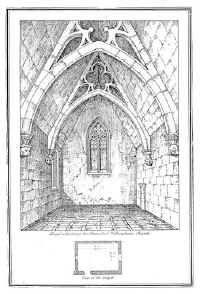

The Sacristy was built onto the north side of

the chancel, a blocked window on the north wall of the chancel indicating

that it was built later. Stylistically the Sacristy is typical of the

first part of the 14th century so it would appear that it was added fairly

soon after the chancel was built, possibly when the tower was being added

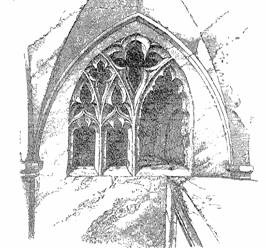

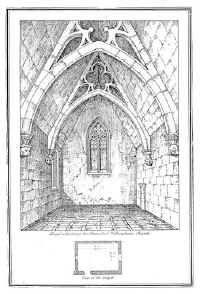

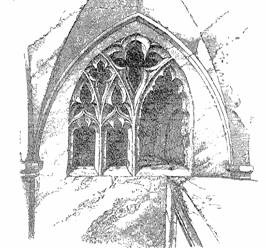

in the 1340s. It measures 4.3 x 3.0 m, has three windows with reticulated

tracery: a tall three-point arched east window, and two square headed

windows, one at low level on the north side and one at high level on the

west side. It has a steep pitched stone roof of Barnack limestone braced

internally with three traceried stone arches. The red tiled floor,

probably Victorian, shows evidence of an altar at the east end beside

which a pedestal-type piscina remains. Access is by means of a pointed

arch doorway from the Chancel and the opening in the masonry is set at a

pronounced angle, orientated on a north west/south east axis. |

19th C. Engraving |

| 8. Evidence for an Anchorhold at

Willingham |

|

|

There are several features of the Sacristy

that suggest its use as an anchorhold and these are:

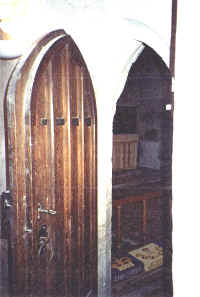

i.) The Squinted Doorway The doorway between the Sacristy and the

Chancel is a 'squint'door, that is an opening that penetrates the thick

wall at an angle. From the plan it can be seen that the angle is directed

toward the east end of the Chancel in such a way that anyone placing

themselves in the Sacristy could just see the altar, and the Blessed

Sacrament that would have been placed there, while remaining virtually

invisible to anyone in the main body of the church. Such an opening is

sometimes referred to as an 'Anchorite's Squint' and was a means of

allowing a recluse to take part in church services, and pray towards the

altar at any time of the day or night, without being seen. There is no

sign that the doorway was at any time less than doorway height and from

this we can assume that - if this was indeed an anchorhold - it was the

type that allowed people to access the cell. There is a small rectangular

niche, to the east of the doorway on the Chancel side that may have served

as a small window to the cell. Perhaps the doorway was cut and the smaller

opening blocked up when the practice of walling in anchorites fell out of

favour.

ii.) The World-Side Window The small window on the north side of the

Sacristy measures approximately 900mm high and 600mm wide. Being only 1.3m

above floor and external ground level this would have made a perfect

'parlour' or 'world-side' window for an anchorite. One can just imagine

villagers coming to this window for advice, to ask for prayers to be said,

or to pass in food, drink and alms.

iii.) Window Hanging Small pockets can be seen either side of the east

window. Prior to the window being glazed, much later than the 14th century

when it was built, these might have provided hanging points for curtains

that would give any inhabitant some degree of shelter from the cold.

iv.) Stone Bed During the conservation works a cement repair at low

level on the north side of the Sacristy was stripped revealing that the

wall behind was constructed of rubble rather than the ashlar work of the

main structure above. Measuring approximately 3m long and 700mm high the

construction suggests that something was built in at this point, possibly

a bed constructed of stone for an inhabitant to sleep on and at one end

sit at the 'world-side' window (see inside elevation looking north).

v.) Location It has been mentioned how anchorholds were frequently

placed on the north side of churches, to deprive them of warmth and sun

and so increase the degree of penance being offered by its inmate. It is

also clear that a position by the chancel was preferred so that the

anchorite could view and take part in the Sacraments. From these

requirements R.M. Clay deduces that "traces of the anchorage… may

reasonably be sought near the chancel [note] and

she mentions various north side anchorholds in her text [note].

vi.) Architectural Style and Scale There is no doubt that a great deal

of care went into the construction of the Sacristy and its level of

detailing suggests a devotional use that nevertheless needed to be

expressed with a minimum of decorative fuss. Examples of traceried windows

carved into hermit's caves (illus.Warkworth Hermitage) and the

illustrations of anchorite's cells in mediaeval manuscripts (illus. St

Fremund) show the same delicate balance between austerity and numinance

that often appears to be invested in such structures. The size is also

what might be expected of a cell to hold a single anchorite. At 140 square

feet it is almost exactly the area recommended in a Bavarian anchoritic

rule-book which dictated that the cell be of stone, 12 feet square [note].

vii) The Altar and Piscina It is clear that at some point there would

have stood an altar at the east end of the Sacristy and the stone piscina

on the south wall beside it would have allowed the safe disposal of holy

water into the consecrated ground as was the custom. We know that altars

were often provided in anchorholds either because the anchorite himself

was a celebrant; to provide for the anchorite's own devotions, or to allow

a visiting priest to say mass in the cell.

viii) Saint Christopher A famous hermit from the 3rd century AD was St

Christopher who, it is said, carried a child across the river only to find

that he had transported Christ who had manifested Himself in infant form.

One of the largest wall paintings on the nave wall at St Mary and All

Saints is of St Christopher in the act of carrying the infant Christ.

Could this demonstrate a particular connection between the church and

those who chose to live a hermitic life? |

The squint door and niche from the chancel (note blocked chancel window

above door)

Looking through the squint door to the altar

The stone arches and west window

The piscina |

| 9. Conclusions and Suggested

Research |

|

|

Clearly no firm conclusions can be drawn from

the above, the evidence being no more than circumstantial. It is

interesting to note, however, the sheer quantity of anchorholds that must

have existed in mediaeval times and contrast this with our scant knowledge

of where they might have been. There does appear to be a burgeoning

interest in these fascinating structures, and the cultural legacy left by

their inhabitants, as the anchoritic conferences held at the University of

Wales in Cardiff, and the recent founding in the United States of the

Anchoritic Society, attest.

To discover whether the Sacristy at Willingham really was an anchorhold

certain steps could be taken, invasive and non-invasive. X-Ray analysis of

the floor might reveal further evidence of a stone bed, a latrine or any

significant burials, without damage to the structure. Careful excavation

could follow and, since the tiled floor is not significant, disturbance to

historic fabric may be kept to a minimum. A similar investigation could be

made of the niche in the Chancel wall that may once have connected with

the Sacristy.

Further historical research may also produce evidence; records of

benefactions are a good source for this type of examination. Dowsing (or

'divining') has also been suggested but this may not be desirable for

liturgical reasons.

We believe the circumstantial evidence for an anchorhold at St Mary and

All Saints is so strong, and the subject so fascinating, that further

research would be fully justified. To provide a sensible plan of action

and determine what costs might be involved we recommend that the Parochial

Church Council seeks the advice of an archaeologist. |

|

| Jeremy Lander, Freeland Rees

Roberts Architects |

|

| Footnote [1] |

The appendix of Rotha Mary Clay's book The

Hermits and Anchorites of England 1914 (RMC) lists nearly 300 anchorites

and maintains this must be a fraction of the actual number as records are

limited and few physical remains of cells survive. From this one can

surmise that between the 12th and early 16th centuries virtually every

parish in England would at some time have had an anchorite living in some

part of the village. |

|

| Footnote [2] |

RMC p 81 |

|

| Footnote [3] |

Matthew Alexander Tales of Old Surrey1985 |

|

| Footnote [4] |

RMC p 94 |

|

| Footnote [5] |

Rotha Mary Clay (RMC) p 79 |

|

| Footnote [6] |

RMC p 73 |

|

| Footnote [7] |

RMC p 103 |

|

| Footnote [8] |

Ancren Riwle |

|

| Footnote [9] |

RMC |

|

| Footnote [10] |

RMC p 122 |

|

| Footnote [11] |

Matthew Alexander |

|

| Footnote [12] |

Ancren Riwle |

|

| Footnote [13] |

There are fragments of Saxon and Norman church

in the south porch put there by the Rector John Watkins during his

restoration 1880s |

|

| Footnote [14] |

Canon Bywater (rector 1937-65) |

|

| Footnote [15] |

RM Clay p 84 |

|

| Footnote [16] |

Examples include: North side of chancel:

Leatherhead, Michaelstow in Cornwall, Newcastle; w. end of n. aisle:

Hartlip, York (All Saints); n.side of w. tower: Chester le Street;

n.(unspecified) Bengeo, Chipping Ongar |

|

| Footnote [17] |

RMC p 79 |

|